Introduction

Banks1 serve an essential role in their communities by providing commercial real estate (CRE) financing. In fact, more than 98 percent of banks engage in CRE lending and CRE loans are the largest loan portfolio type for nearly half of all banks. The dollar volume of CRE loans is at an historic high, and a growing number of banks report CRE concentrations. But lending concentrations – sometimes a necessity of doing business, particularly for smaller banks – are not by definition problematic. The majority of banks with CRE loan concentrations are satisfactorily rated. Nevertheless, CRE loan concentrations add dimensions of risk that necessitate continued attention from banks and their regulators, especially as the pandemic lingers and uncertainties remain.

This article examines the financial performance and credit quality metrics of CRE-concentrated banks through year-end 2021, as well as pandemic impacts on CRE markets. The article also provides examination observations about CRE lending risk management practices. Lastly, the article discusses the FDIC’s supervisory focus for banks with significant CRE portfolios.

CRE Lending is a Significant Business Line for Many Banks

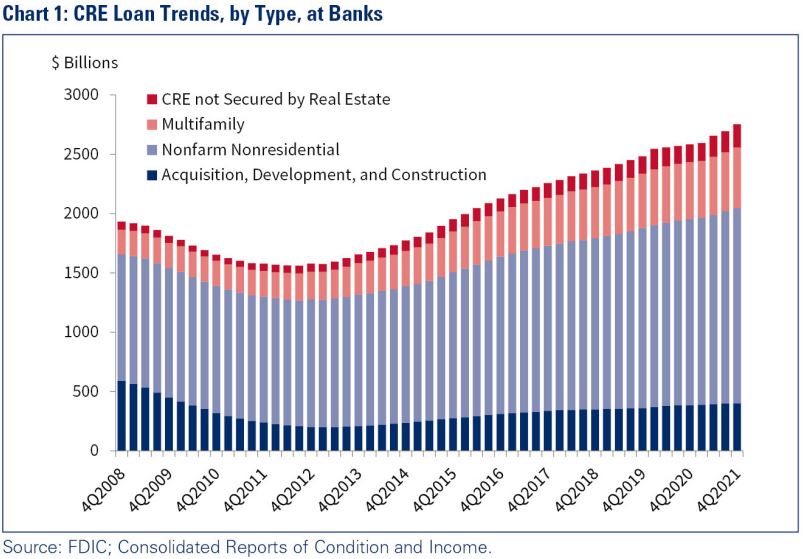

Banks remain heavily engaged in CRE lending with the volume of CRE loans held by banks recently peaking at more than $2.7 trillion. This is well above the $1.9 trillion held in 2008 (see Chart 1). At year-end 2021, FDIC-supervised banks held almost $1.1 trillion in CRE loans.

Community banks, which are largely FDIC-supervised, held $795.7 billion.2 As reported in the FDIC’s fourth quarter 2021 Quarterly Banking Profile (QBP), growth in nonfarm nonresidential CRE loan balances drove that quarter’s increase in community banks’ loan balances.3 In addition, the banking industry is exposed to CRE via holdings of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), albeit below the levels of CRE loan exposures.4

At year-end 2021, 25 percent of banks had a funded CRE loan concentration in excess of 300 percent of tier 1 capital and reserves for loan losses.5 This is relatively unchanged compared to year-end 2019, prior to the pandemic.

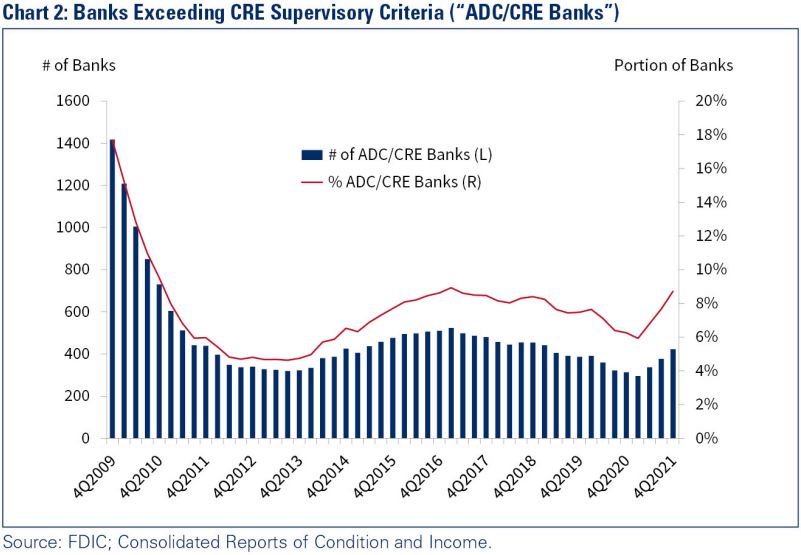

Meanwhile, at year-end 2021, 422 banks met one or both of the supervisory criteria pursuant to the interagency supervisory guidance entitled “Concentrations in Commercial Real Estate Lending, Sound Risk Management Practices,” up from 313 the previous year (see Chart 2).6 One criterion is that total reported loans for construction, land development, and other land represent 100 percent or more of the bank’s tier 1 capital plus the allowance for loan and lease losses (ALLL) or the portion of the allowance for credit losses (ACL) attributable to loans and leases, as applicable (hereafter referred to as the Acquisition, Development, and Construction (ADC) Lender Group). The other criterion is that total CRE loans as defined therein7 represent 300 percent or more of the bank’s tier 1 capital plus the ALLL or applicable portion of the ACL, and the outstanding balance of the bank’s CRE portfolio has increased by 50 percent or more during the prior 36 months (hereafter referred to as the CRE Lender Group).8 These levels are not safe harbors nor regulatory limits. Rather, regulators may identify a bank that is approaching or meets the criteria, or that has notable exposure to a specific type of CRE, for further supervisory analysis. Going forward, this article refers to the ADC Lender Group and the CRE Lender Group as ADC/CRE Banks in aggregate and defines banks not meeting either of the criteria as All Other Banks.

In 2020 and into first quarter 2021, the count of ADC/CRE Banks dipped as in-process construction projects stalled and project starts were delayed in response to the economic impact of pandemic-related shutdowns. Concurrent with easing of the pandemic’s impact on economic activity, lending began to rebound. Largely due to ADC lending, the count of ADC/CRE Banks increased by 127 between the first and fourth quarters of 2021. At about nine percent, the level of ADC/CRE Banks to total banks remains well below the same measure during the Great Recession (see Chart 2). About 70 percent of the ADC/CRE Banks are FDIC-supervised.

Select Performance Trends at CRE-Concentrated Banks

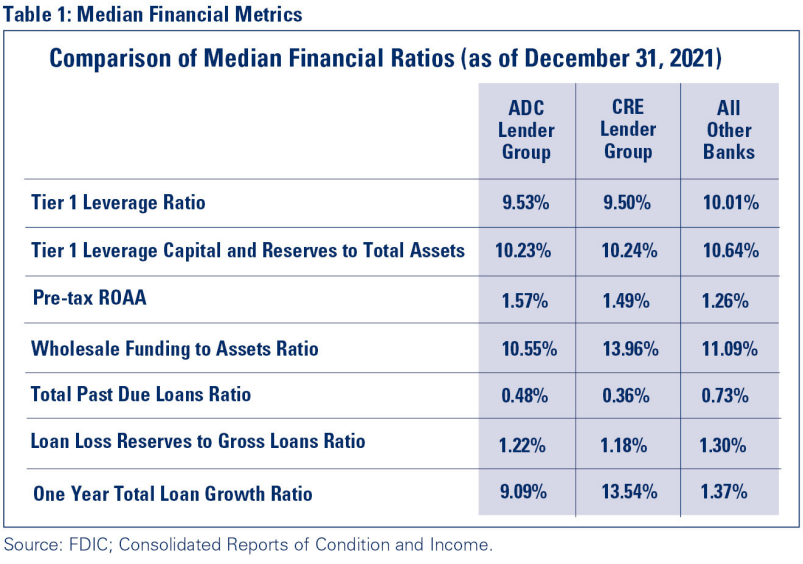

When banks select and underwrite risks prudently and oversee portfolios diligently, consistent with safe and sound lending principles,9 CRE lending can be a profitable business line. As displayed by medians in Table 1, the CRE Lender and ADC Lender Groups currently exhibit higher pre-tax returns on average assets (ROAA) than All Other Banks.10 However, they still operate with a generally higher-risk profile, including lower capital and loan loss reserve levels compared to All Other Banks.

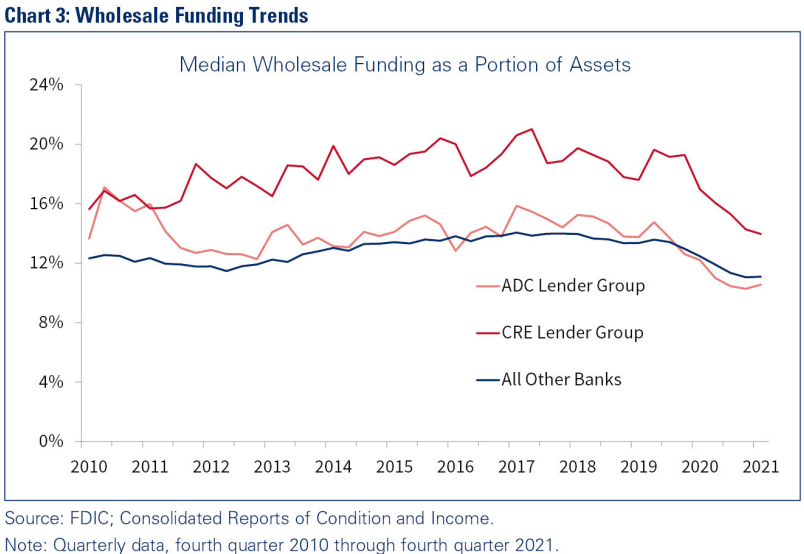

Robust deposit growth, driven by government stimulus and other relief measures enacted during the pandemic, and generally lower overall loan demand led to banks relying less on wholesale funding.11 However, the CRE Lender Group continues to rely on wholesale funding more than the ADC Lender Group and All Other Banks (see Chart 3). As shown in the chart, the ADC Lender Group is the least reliant on wholesale funding among the groups. The ADC Lender Group recently showed a slight upturn in dependence on wholesale funding, not yet indicative of a sustained trend.

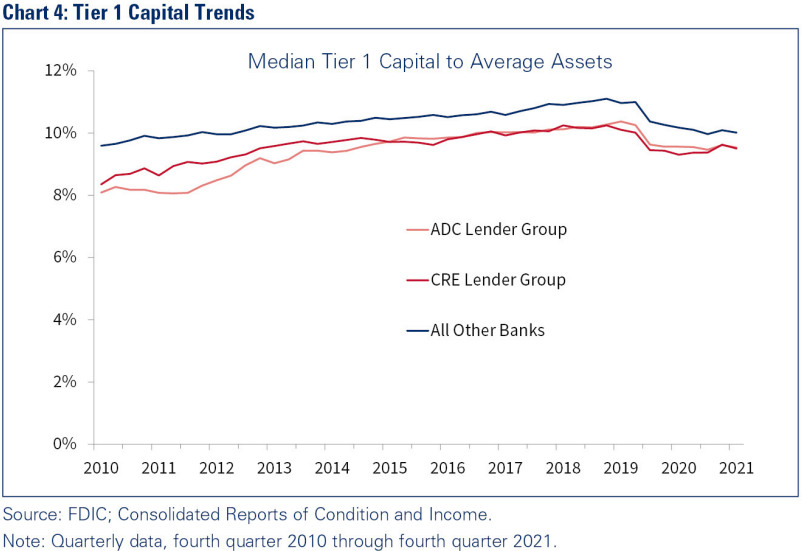

At the median, banks’ capital positions appeared stable during the pandemic. However, the CRE Lender Group and the ADC Lender Group each continued to hold lower capital than All Other Banks (see Chart 4). As part of assessing the adequacy of a bank’s capital, regulators consider the level and nature of inherent risk in the CRE portfolio as well as management expertise, historical performance, underwriting standards, risk management practices, market conditions, and any loan loss reserves allocated for CRE concentration risk.

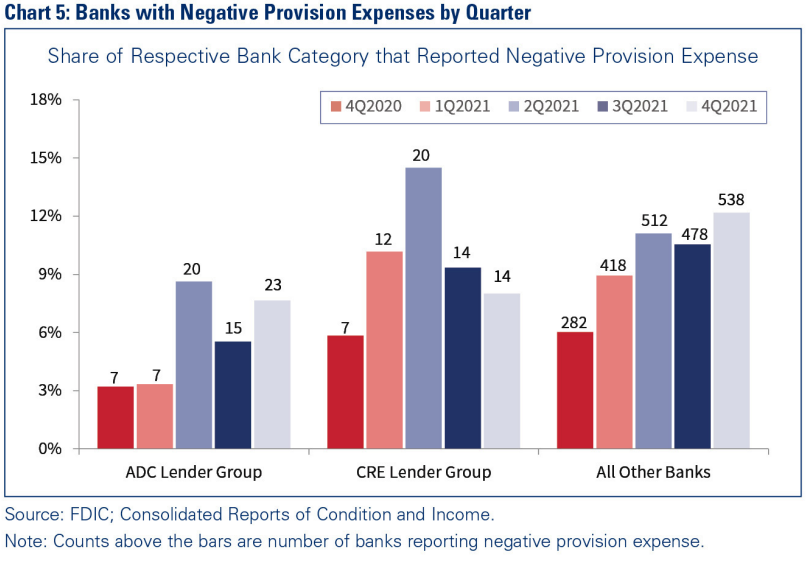

Banks braced for potentially substantive losses across many types of loan portfolios in response to the economic impacts of the pandemic. Efforts by a portion of the industry to adopt the new Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) accounting standard also coincided with the onset of the pandemic. Consequently, provision expenses for the banking industry swelled by $77.1 billion (140 percent) in 2020. The $84.9 billion decline in bank net income as compared to 2019 was primarily due to higher provision expenses in first half 2020, driven by pandemic-related deterioration in economic activity. Conversely, and in tandem with signs of macroeconomic improvement in the wake of substantial government stimulus and losses that had not materialized, the primary driver of higher quarterly net income in the second half of 2020 was a reduction in provision expenses. Negative provisions were a key reason bank net income increased $132.0 billion for the full year 2021 compared to 2020.12 Banks in the CRE Lender Group and the ADC Lender Group were among banks that booked negative provision expenses (see Chart 5).13

As shown previously, in Table 1, ADC/CRE Banks currently hold levels of loan loss reserves to total loans that range eight to twelve basis points lower than the level held by All Other Banks. However, history has demonstrated that CRE portfolios, particularly the ADC subset, have the propensity to produce significant losses during periods of economic stress, especially when not properly managed.

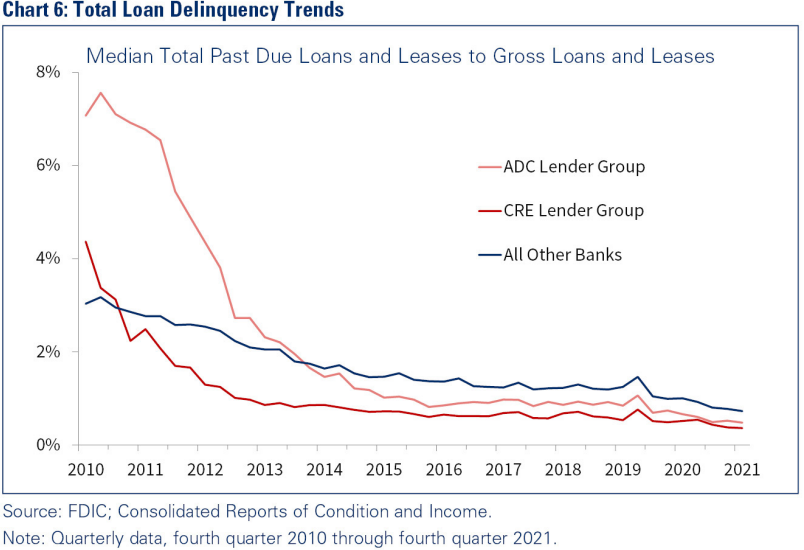

Although most CRE-concentrated banks felt some stress from the pandemic, CRE loan delinquencies are at historically low levels (see Chart 6), and aggregate loan losses have been nominal. These trends are at least partly attributable to stimulus and relief programs as well as low borrowing costs. In addition, banks worked extensively with borrowers experiencing stress during the pandemic, which likely suppressed delinquencies and may have ultimately limited losses by giving borrowers time and flexibility to address issues.

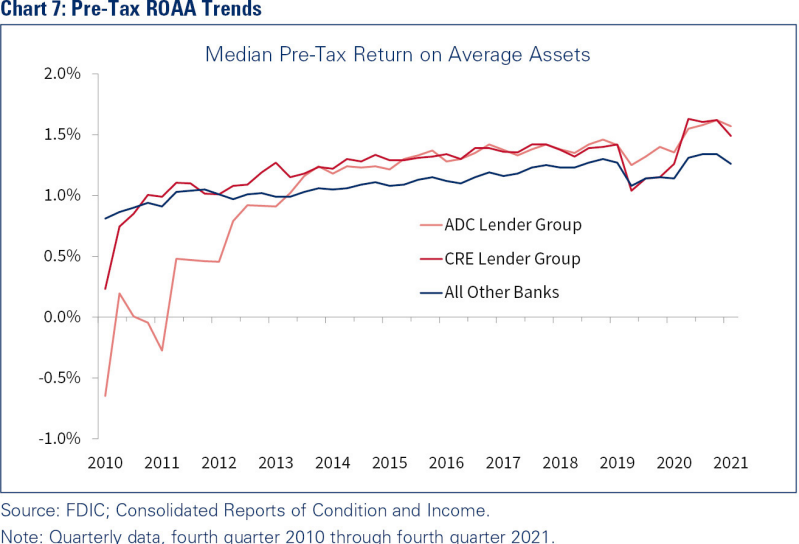

Against the backdrop of low delinquencies and a recovering economy, ADC/CRE Banks are outpacing All Other Banks in terms of pre-tax ROAA (see Chart 7). Their medians are 1.57 percent and 1.49 percent, while the median for All Other Banks is 1.26 percent. The higher returns for the ADC/CRE Banks may reflect, at least in part, the functioning of “higher risk, higher reward,” although many factors complicate the core earnings analysis.

Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) fee income and negative provisions boosted income for many banks in 2021, while reduced overdraft charges and nonsufficient funds fees and elevated liquidity invested in lower yielding assets, along with robust loan competition, served as counterbalances. In addition, other pressures persist on bank earnings. Inflation, competition, and tight labor markets are affecting expenses. Actions such as loosening underwriting in a competitive environment could ultimately hinder future bank earnings if credit quality is compromised, credit relationships are not properly managed, or both.

Certain Pandemic Impacts May be Long Lasting

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led to stress across several CRE property types and tested bankers’ risk management practices. The pandemic’s initial impact across certain CRE sectors was severe. Hotel vacancies were significant; many office employees began working from home; and foot traffic at retail shopping centers, restaurants, and entertainment spaces ground to a halt.

Certain CRE sectors largely held up or recovered quickly, such as industrial properties and multifamily properties; although even within these sectors, strength and recovery has not been even across geographies. The significant increase in demand for industrial warehouse space to meet the rise in e-commerce helped that sector exceed pre-pandemic performance. In other cases, the pandemic exacerbated trends affecting CRE use, such as the move away from brick-and-mortar shopping venues and the increasing preference for work-from-home options, particularly in densely populated metropolitan areas.

During the pandemic, the federal banking regulatory agencies (agencies)14 issued regulatory and banking supervision measures which, among other purposes, encouraged bankers to work with adversely affected customers and communities (see inset box below).

Although some of the economic effects of the pandemic appear to be easing, some of its impacts may be lasting, or may have exacerbated existing secular trends, or both. “Commercial Real Estate: Resilience, Recovery, and Risks Ahead,” a featured article in FDIC Quarterly, further explores recent CRE market conditions and the challenges ahead.15 According to the article, the delinquency rates for CMBS backed by hotel and retail properties reached double digits in 2020, surpassing peak rates in the previous real estate cycle. While more recently improved, the delinquency rates remain above pre-pandemic levels. The article indicates that economic stress caused by the pandemic is one of the challenges facing the CRE industry and the lending landscape.

Results of the 2021 Shared National Credit (SNC) Review echo sentiments that challenges lie ahead and that CRE warrants attention.16 The SNC press release notes year-over-year weakening in CRE, demonstrated by a higher classified rate for CRE as well as increasing levels of CRE loans listed for Special Mention, with risk most evident in the hotel, office, and retail sub-sectors. As stated in the release, the direction of risk may be affected by the level of success in managing the pandemic and by other concerns, including inflation, supply chain imbalances, labor challenges, and vulnerability to rising interest rates. These additional risks could adversely affect the financial condition and repayment capacity of borrowers in a variety of industries.

Observed CRE Lending Risk Management Practices

Throughout the pandemic, the FDIC continued to perform risk management examinations and other supervisory activities, predominantly in an offsite capacity. Assessing the effectiveness of banks’ CRE lending risk management practices has remained a critical part of the FDIC’s forward-looking, risk-focused supervision.

Overall, banks with comprehensive, well-developed risk management practices generally adapted better during the pandemic. For banks substantively involved in CRE lending, this was especially true when robust contingency planning and stress testing/scenario analysis processes were in place. For the most part, banks focused on CRE lending have exhibited satisfactory risk management practices. However, a few themes emerged as opportunities for improvement, as summarized below.

Governance, Credit Underwriting, Risk Management Practices

Over the 2021 examination cycle, FDIC examiners observed a notable level of loan policy exceptions as well as opportunities for improvements in tracking and monitoring policy exceptions. Additionally, examiners noted some areas of underwriting weaknesses.

Assessing repayment capacity is one of the more common credit underwriting concerns that examiners have reported through supervisory recommendations.17 The pandemic has complicated repayment capacity analyses. For example, considerations include when and how to consider PPP loan funds, stimulus funds, or other relief-driven support. Given the temporary nature and wind-down of many support measures, a reasonable path observed by examiners is to obtain the most relevant projections available and also consider whether and how the borrower’s business is expected to rebound and replace the interim support measures. Nevertheless, examiners have observed other instances of stale financial information and unsupported projections underpinning repayment capacity analyses.

Continued uncertainties surrounding economic forecasts combined with varying pandemic impacts by sector and geography also present bankers and appraisers with challenges in developing well-supported and timely collateral valuations for CRE properties. While 2021 saw improvement in the commercial property market compared to 2020, some sectors, such as hotel (particularly those that are business/ convention-oriented) and office, and some geographies, such as the Manhattan borough of New York City, lagged. In another example, the previously referenced FDIC Quarterly article discusses observed declines in shopping mall valuations in 2021.18 Pandemic impacts and other uncertainties remain poised to potentially affect CRE property values.

Credit Risk Rating Systems

A strong credit review function is critical for a bank’s self-assessment of emerging risks. An effective, accurate, and timely risk rating system provides the foundation for the credit risk review function to assess credit quality, and, ultimately, to identify problem loans.

Recent assessments of bank-assigned borrower risk ratings revealed that many banks identified at least some credit deterioration since the onset of the pandemic that warranted more severe risk ratings. Deterioration was primarily limited to shifts within non-classified rating tiers. In more severe cases, the pandemic generally exacerbated pre-existing credit problems. Although banks are taking steps to update borrower risk ratings and watch lists, in some instances examiners assigned more severe risk ratings.

Risk rating frameworks justifiably vary from bank-to-bank. However, examiners sometimes found that rating frameworks were largely judgmental and lacked an element of well-defined, objective financial metrics or criteria to differentiate meaningfully between, and appropriately rank-order, internally assigned risk grades. In response to the pandemic, some banks suspended, modified, or added new categories to existing frameworks. Generally, examiners caution that suspending a risk rating framework during periods of stress, even when unprecedented, may ultimately hinder longer-term efforts to conduct meaningful historical migration analysis and could present near-term challenges for timely identification of problem assets. Adding new categories to, or modifying existing categories within, current risk rating frameworks may be appropriate when notable risk identification gaps or weaknesses have become apparent.

Market Analysis

With consideration of the real estate lending standards appended to Part 365 of the FDIC’s Rules and Regulations,19 the vast majority of banks with elevated CRE exposure are performing some type of market analysis, although the level of formality varies. Some banks do not refresh their analyses as frequently as warranted, have applied segmentation techniques ineffectively, or have not drawn conclusions from the analyses performed. A thorough understanding of the current and forward-looking economic and business factors influencing markets is particularly important for making safe and sound decisions about entering new markets, pursuing new lending activities, or reducing or expanding investment in existing markets. When performed well, market analysis can help generate reasonable assumptions for use in planning and modeling and can assist bank management in avoiding bad investments.

Management Information Systems

Accurate, reliable, and timely data and reporting at the portfolio and loan levels are also critical to support business decisions. Examiners have observed some instances of insufficient policy exception reporting and tracking. In addition, at some banks, loan-level data were missing or were derived pre-pandemic and, therefore, were not as useful in understanding portfolio stress. For example, net operating income, debt service coverage, or loan- to-value metrics were sometimes absent, out-of-date, or limited to a stand-alone entity basis (rather than considering the cumulative relationship).

Stress Testing and Sensitivity Analyses

It is important for bank management to understand how risk in a bank’s loan portfolio can affect its financial condition. A common way to do this is through portfolio stress testing and sensitivity analyses. A review of supervisory recommendations included in Reports of Examination indicates there are opportunities for improvement in this area.

Some banks with significant CRE portfolios have not performed sufficient risk analysis, despite elevated risk profiles. Others have not addressed the board of directors’ expectations with respect to such testing and analysis in their policies. In addition, examiners observed that the design and complexity of some testing or analysis methods were inconsistent with the nature of the CRE portfolios and lending environments. For example, examiners have observed that banks with CRE concentrations in multiple geographies sometimes applied broad stress assumptions to the entire portfolio instead of considering relevant variations in market conditions across the geographies. In other cases, stress testing time horizons did not align with the amortization periods or construction timelines typical of the bank’s CRE product offerings. These inconsistencies may ultimately weaken the usefulness of the results for the bank’s board of directors and management.

Other concerns noted included the quality and quantity of data inputs and insufficient magnitude of stress levels applied. Additionally, sometimes, management did not consider how results would impact the bank’s capital and asset quality. This final step in the stress testing process provides critical capital planning information to the bank’s board of directors.

The FDIC’s Supervisory Approach to CRE in the 2022/2023 Examination Cycle

In addition to continuing to monitor for emerging systemic changes in CRE segments across the nation, the FDIC expects to continue its existing supervisory approach for banks with CRE concentrations. The June 2020 Interagency Examiner Guidance for Assessing Safety and Soundness Considering the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Financial Institutions (Examiner Guidance)20 acknowledges that stresses caused by COVID-19 can adversely affect a bank’s financial condition and operational capabilities, even when bank management has appropriate governance and risk management systems in place to identify, monitor, and control risk. The Examiner Guidance also instructs agency staff to continue to assess banks in accordance with existing policies and procedures,21 which may result in supervisory feedback, or changes to a bank’s composite or component ratings, when conditions or risk management practices warrant as such.

Examiners will consider the unique, evolving, and potentially long-term nature of the issues confronting banks in developing their supervisory response. For example, appropriate actions taken by banks in good faith reliance on such statements, within applicable timeframes described in such statements, will not be subject to criticism or other supervisory action. As another example, in considering the supervisory response for banks accorded a lower supervisory rating, examiners will give appropriate recognition to the extent to which weaknesses are caused by external economic problems related to the pandemic versus risk management and governance issues.

Per the Examiner Guidance, examiners will consider the bank’s asset size, complexity, and risk profile, as well its customers’ industry and business focus.

As a continuance of the FDIC’s longstanding risk-focused and forward- looking supervision principle, FDIC examiners prioritize resources toward areas presenting the highest risk at an individual bank, which often includes significant CRE lending concentrations. Among other provisions, the Examiner Guidance conveys that examiners will continue to:

- Assess credit quality in line with the interagency credit classification standards, while recognizing the constraints posed by the pandemic,

- Assess management’s ability to implement prudent credit modifications and underwriting, maintain appropriate loan risk ratings, designate appropriate accrual status on affected loans, and provide for an appropriate reserve for credit losses, and

- Assign supervisory ratings in accordance with the applicable rating systems.

When assigning the composite and component ratings, examiners review management’s assessment of risks presented by the pandemic, in the context of the bank’s size, complexity, and risk profile. When assessing management, examiners will consider management’s effectiveness in responding to the changes in the bank’s business markets and whether management’s longer-term business strategies address these changes.

Given the uncertain long-term impacts of changes in work and commerce in the wake of the pandemic, the effects of rising interest rates, inflationary pressures, and supply chain issues, examiners will be increasing their focus on CRE transaction testing in the upcoming examination cycle. In particular, examiners will be testing newer CRE credits, credits within stressed sub-categories and geographies, and credits with payments vulnerable to rising rates and rising costs.

Conclusion

CRE lending remains an important aspect of bankers’ efforts to support their communities, including in response to the still-evolving impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The FDIC recognizes these efforts, when prudently undertaken and consistent with safe and sound banking practices, serve the public interest. As a result, the FDIC continues to encourage and support banks in taking prudent steps to assist affected customers. Examining the effectiveness of governance and risk management practices related to CRE lending will remain a supervisory priority.

Lisa A. Garcia

Senior Examination Specialist

Division of Risk Management Supervision

ligarcia@fdic.gov

Ryan J. Gullett

Senior Examination Specialist

Division of Risk Management Supervision

rgullett@fdic.gov

Yelizaveta (Leeza) Shapiro

Senior Quantitative Risk Analyst

Division of Risk Management Supervision

yshapiro@fdic.gov

Jeffrey W. Stanovich

Senior Examination Specialist

Division of Risk Management Supervision

jstanovich@fdic.gov

1 For purposes of this article, the term “banks” refers to FDIC-insured depository institutions.

2 “Community banks” refer to FDIC-insured institutions meeting the criteria for community banks described in the FDIC Community Banking Study published in December 2020. See page A-1 at https://www.fdic.gov/resources/community-banking/report/2020/2020-cbi-study-full.pdf.

3 See the QBP at https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/qbp/2021dec/qbp.pdf. The community bank performance section starts on page 15 of that report; loan growth comments begin on page 16.

4 See “CRE: Resilience, Recovery, and Risks Ahead” within FDIC Quarterly, 2021, Volume 15, Number 4, at https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/2021-vol15-4/article1.pdf.

5 This measure is not a regulatory limit nor is it a safe harbor. For purposes of this article, concentration calculations do not consider unfunded commitments.

6 See FIL-104-2006, “Commercial Real Estate Lending Joint Guidance,”at https://www.fdic.gov/news/financial-institution-letters/2006/fil06104.html.

7 Essentially defined as non-owner occupied.

8 At the end of the fourth quarter 2021, the ADC Lender Group was comprised of 301 banks and the CRE Lender Group was comprised of 175 banks (54 banks met both prongs).

9 Section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance (FDI) Act requires the FDIC to establish safety and soundness standards. For FDIC-supervised banks, Part 364 of the FDIC Rules and Regulations establishes safety and soundness standards by guideline, as set forth in its Appendix A, Interagency Guidelines Establishing Standards for Safety and Soundness. Refer to the guidelines at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-12/chapter-III/subchapter-B/part-364. Also, Section 18(o) of the FDI Act requires the federal banking agencies to adopt uniform regulations prescribing standards for loans secured by liens on real estate or made for the purpose of financing permanent improvements to real estate. Subpart A of Part 365 of the FDIC Rules and Regulations prescribes standards for real estate lending to be used by FDIC-supervised banks in adopting internal real estate lending policies. Refer to Part 365 and its Appendix A to Subpart A, Interagency Guidelines for Real Estate Lending Policies, at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-12/chapter-III/subchapter-B/part-365.

10 This article displays financial metrics for banks as medians to reflect the “typical” bank in the relevant categories rather than as averages, which outliers can distort.

11 For the purposes of this article, wholesale funding is defined primarily as the sum of the following Call Report categories: federal funds purchased and securities sold under agreements to repurchase, other borrowed money, brokered deposits, deposits gathered through listing services, and uninsured deposits of state and political subdivisions. This is for analysis purposes only and does not constitute an official regulatory definition.

12 See QBPs at https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/

13 Thirty-three of the ADC/CRE Banks adopted CECL through fourth quarter 2021. Sixteen of the 33 had negative provisions in 4Q2021; the 16 included nine from the ADC Lender Group and seven from the CRE Lender Group. In all, 310 banks adopted CECL through fourth quarter 2021, and 144 of those 310 had negative provisions in fourth quarter 2021.

14 The federal banking regulatory agencies include the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Board), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).

15 See “CRE: Resilience, Recovery, and Risks Ahead” within FDIC Quarterly, 2021, Volume 15, Number 4, at https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/2021-vol15-4/article1.pdf

16 See Agencies Issue 2021 Shared National Credit Review, FDIC: PR-18-2022, February 14, 2022 at https://www.fdic.gov/news/press-releases/2022/pr22018.html.

17 The FDIC intends supervisory recommendations, which are conveyed to banks in writing, to inform the bank of the FDIC’s views about changes needed in its practices, operations, or financial condition. Conditions leading to supervisory recommendations generally are correctable in the normal course of business; however, material issues and recommendations that require the attention of the institution’s board of directors and senior management are communicated using a subset of supervisory recommendations referred to as Matters Requiring Board Attention. For more detail, refer to the Statement of FDIC Board of Directors on the Development and Communication of Supervisory Recommendations at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/examinations/supervisory/guidance/recommendations.html.

18 See page 35 of the FDIC Quarterly article referenced in footnote 4.

19 See footnote 9.

20 See the Financial Institution Letter related to the Examiner Guidance, FIL-64-2020, at https://www.fdic.gov/news/financial-institution-letters/2020/fil20064.html.

21 The Examination Documentation (ED) Modules are a tool used by FDIC examiners to carry out forward-looking, risk-focused examination programs. Because the ED Modules may not address every risk consideration, examiners have the discretion to perform and document additional examination procedures to assess risk, as needed. Refer to the ED Modules at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/safety/manual/section22-1/index.html.