Introduction

Financial institutions play a crucial role in our nation’s efforts to combat financial fraud, money laundering, and the financing of terrorism through their compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). These crimes pose a critical challenge to the integrity and security of, as well as public confidence in, our financial system and can impact our national security. The FDIC and other financial regulatory agencies conduct BSA examinations to assess whether depository institutions have established and maintained BSA compliance programs commensurate with their money laundering and terrorist financing risk. Although deficiencies may be identified during examinations, the vast majority of FDIC-supervised institutions are able to address any BSA compliance deficiencies identified through the supervisory process in the normal course, without the need for a formal enforcement action. However, there are limited instances where such deficiencies constitute a BSA compliance program problem that necessitates formal remediation.

This article describes the BSA, provides a short BSA history, conveys how BSA compliance is examined by the FDIC, and contains examples of the limited instances where a BSA-related formal enforcement action was necessary.

What is the Bank Secrecy Act and Why is it Important?

The BSA is the common name for a series of laws and regulations that have been enacted in the United States to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism. The BSA provides a foundation to promote financial transparency and deter and detect those who seek to misuse the U.S. financial system to launder criminal proceeds, finance terrorist acts, or move funds for other illicit purposes.

Under the law, financial institutions have a responsibility to monitor for suspicious activities and to identify and report those suspicious activities to law enforcement. Identifying and reporting suspicious financial transactions are critical to law enforcement’s ability to combat drug trafficking, organized criminal activity, and terrorism. Financial institution reporting has been instrumental in the successful investigations of fraud schemes, drug trafficking, money laundering, foreign terrorist fighters, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.1

BSA History

The BSA has evolved from currency transaction reporting requirements to include required BSA compliance programs, suspicious activity monitoring, and other reporting requirements aiming to better identify money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit financial activities. To understand the regulatory framework as it exists today, it is important to provide the historical context for certain anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) laws.

When Congress enacted the BSA in 1970, its primary intent was to require institutions to maintain certain records the government could use to support criminal and tax evasion investigations. The Bank Records and Foreign Transaction Act, or BSA, addressed two issues that were impeding law enforcement agencies’ ability to investigate and prosecute criminal activity: the lack of financial recordkeeping by financial institutions and the use of foreign bank accounts located in jurisdictions with strict secrecy laws. Although the initial enactment of the BSA sought to support criminal investigations related to the illegal movement of funds by requiring currency and foreign bank account reporting requirements, the act of money laundering itself was not considered illegal in the U.S. until sixteen years later.

Along with criminalizing money laundering and prohibiting the act of structuring transactions to evade reporting requirements, the Money Laundering Control Act of 1986 addressed the federal financial regulatory agencies’ (Agencies) 2 supervision and enforcement authorities. The act added requirements that are prominent in today’s administration of the BSA. Namely, it required the Agencies to examine for BSA compliance during each examination cycle, issue regulations requiring depository institutions to establish and maintain BSA compliance procedures, and issue cease and desist orders to address a depository institution’s failure to establish and maintain BSA compliance procedures or failure to correct a previously identified problem with its BSA compliance procedures.

Subsequent to the enactment of the Money Laundering Control Act, the Agencies issued regulations requiring depository institutions to establish and maintain BSA compliance programs. This requirement provided an early framework for supervision and enforcement of compliance with the BSA.

In 1992, Congress enacted the Annunzio-Wylie Anti-Money Laundering Act, which established suspicious activity reporting and funds transfer recordkeeping requirements. It also included a provision giving certain Agencies the authority to revoke banking charters or to terminate deposit insurance for institutions convicted of a money laundering offense after one of the “earliest glaring examples of financial crime perpetrated by and through an international banking institution”3 was brought to light.

The Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) was operating in 78 countries and held assets of more than $20 billion when regulatory and law enforcement authorities in a number of jurisdictions discovered that the institution was a massive conduit for money laundering and other financial crimes, and had illegally acquired a controlling interest in a U.S. institution. Before it was closed in 1991, BCCI had provided banking services to a number of senior foreign political figures, often referred to as “politically exposed persons,” such as Saddam Hussein, Manuel Noriega, and Abu Nidal, as well as to the Medellin Cartel.

By the end of the century, several legislative initiatives addressed the movement of illicit funds through an increasingly global financial system; however, forthcoming events would emphasize the urgency to enact preventative measures under the BSA. The attacks of September 11, 2001, underscored the relationship between financial crime and terrorist financing in that terrorist groups use methods similar to those of money launderers and criminal organizations to avoid detection. The need to identify and report suspicious financial transactions that may be supporting terrorism was recognized as a necessary element in the fight against terrorism. Shortly thereafter, Congress passed the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act in October of 2001.

The USA PATRIOT Act is one of the most significant AML/CFT laws that Congress has enacted since the BSA itself. Among other things, the law criminalized the financing of terrorism, authorized the Agencies to impose customer identification requirements on financial institutions, established information sharing provisions, and required enhanced due diligence by financial institutions for certain foreign correspondent and private banking accounts.

Another notable change implemented by the USA PATRIOT Act was to elevate the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network4 (FinCEN) from an office to a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. FinCEN is the designated administrator of the BSA and serves as the financial intelligence unit of the United States. In its capacity as administrator, FinCEN issues regulations and interpretive guidance, provides outreach to regulated industries, supports the examination functions performed by federal and state agencies, and pursues civil enforcement actions when warranted. FinCEN’s other responsibilities include collecting, analyzing, and disseminating information received from institutions subject to the BSA, and identifying and communicating financial crime trends and patterns. Importantly, FinCEN has delegated much of its examination authority to regulatory agencies, including the FDIC.

How is BSA Compliance Examined?

The evolution of the BSA lays the foundation for the current AML/CFT framework. Law enforcement and regulatory agencies play a role related to BSA/AML compliance. The FDIC and state bank regulatory agencies5 conduct BSA/AML examinations for insured state nonmember institutions.6

During each safety-and-soundness examination, the FDIC evaluates the institution’s compliance with the BSA and its implementing regulations 7 as well the FDIC’s own BSA compliance program 8 and suspicious activity reporting 9 requirements. The focus of a BSA/AML examination is to assess whether the institution has established and maintains a BSA compliance program that is commensurate with the institution’s money laundering and terrorist financing risks.

Under Section 8(s) of the Federal Deposit Insurance (FDI) Act, the FDIC is directed to prescribe regulations requiring each FDIC-supervised institution to establish and maintain procedures reasonably designed to assure and monitor the institution’s compliance with the requirements of the BSA and its implementing regulations.10 Section 326.8 of the FDIC’s Rules and Regulations implements Section 8(s) of the FDI Act and establishes a BSA compliance program requirement. Under Section 326.8, an FDIC-supervised institution’s BSA compliance program must contain the following components:

- A system of internal controls to assure ongoing compliance with the BSA;

- Independent testing for BSA compliance;

- A designated individual(s) responsible for coordinating and monitoring BSA compliance; and

- Training for appropriate personnel.

In addition, a BSA compliance program must include a customer identification program (CIP) with risk-based procedures that enable the institution to form a reasonable belief that it knows the true identity of its customers.

Section 8(s) of the FDI Act also provides that the FDIC shall issue a cease and desist order against an FDIC-supervised institution that has failed to establish and maintain a BSA compliance program or has failed to correct any problem with its BSA compliance program that was previously reported to the institution. To be an uncorrected problem with the BSA compliance program that will result in a cease and desist order under Section 8(s), deficiencies in the BSA compliance program must be identified in a report of examination or other written document as requiring communication to an institution’s board of directors or senior management for correction.

The FDIC implements a risk-based approach to assess compliance with the BSA and considers an institution’s risk profile and potential exposure to money laundering and terrorist financing. When BSA compliance deficiencies are identified, they are communicated to an institution’s management through a variety of channels including informal discussions during the examination process, formal discussions following the examination process, findings in reports of examinations, or other formal communications. The particular method of communication used typically depends on the seriousness of the concerns.

In cases in which prompt remedial action is not taken by management, corrective actions are not effectively implemented, or there are serious concerns related to the compliance deficiency, the FDIC will consider a range of corrective options based on the severity of the deficiency, management’s willingness and ability to correct the deficiency, and the money laundering and terrorist financing risk posed to the institution. These corrective options include informal enforcement actions such as memoranda of understanding and formal enforcement actions such as cease and desist or consent orders.

The Interagency Statement on Enforcement of Bank Secrecy Act/Anti- Money Laundering Requirements 11 details circumstances in which the FDIC will issue a cease and desist order to address noncompliance with BSA/AML requirements. The guidance discusses instances in which formal enforcement actions will be issued for BSA compliance program problems and failures under Section 8(s) of the FDI Act.

What Does the FDIC Find in its BSA Examinations?

In the vast majority of examinations, the FDIC finds that institutions generally comply with the BSA. When examiners find BSA compliance deficiencies, they are often technical recordkeeping or reporting matters that can be addressed in the normal course of business.

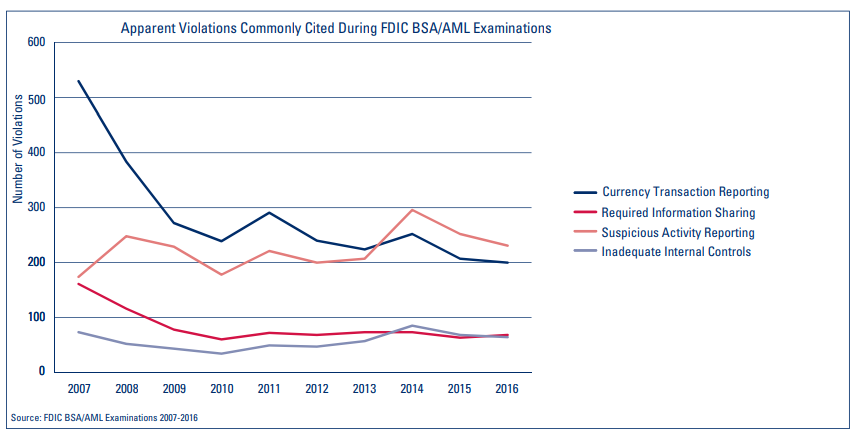

The most common apparent violations of BSA regulations that are cited during the FDIC’s BSA/ AML examinations are related to currency transaction report filings and information sharing requirements. Common violations under the FDIC’s BSA compliance program and suspicious activity reporting requirements relate to suspicious activity report filing deficiencies and inadequate systems of internal controls. The table below illustrates the number of aforementioned apparent violations that were cited over the previous 10 years.

Institutions can prevent compliance deficiencies related to these commonly cited violations by maintaining effective BSA/AML internal control structures. For example, information sharing compliance deficiencies may be corrected by designating persons responsible for conducting searches, keeping contact information up to date with FinCEN, and establishing policies, procedures and processes that clearly outline methods for conducting and documenting information sharing request searches, as well as reporting the results of those searches, as necessary.

Compliance deficiencies related to suspicious activity reporting can be prevented with trained staff and the implementation of systems to identify, research, and report unusual activity. Training and systems should be commensurate with an institution’s overall risk profile and include effective decision-making processes. Effective decision-making processes should be supported by adequate documentation regarding decisions to file or not to file a suspicious activity report (SAR). Because SAR decision making requires review, analysis, and judgment of transactions, institutions should maintain effective internal control systems that establish appropriate policies, procedures, and processes for suspicious activity monitoring and reporting.

BSA compliance deficiencies range from technical violations of BSA regulations, such as a failure to file a timely currency transaction report (CTR) to more severe BSA compliance program failures. Technical violations alone do not warrant criticism of an institution’s BSA compliance program, but may be indicators of more significant deficiencies with BSA compliance program components. For instance, multiple apparent violations for failure to file CTRs may be the result of deficiencies in the institution’s monitoring process and could be indicative of a problem with one or more BSA compliance program components, such as the internal controls and training components.

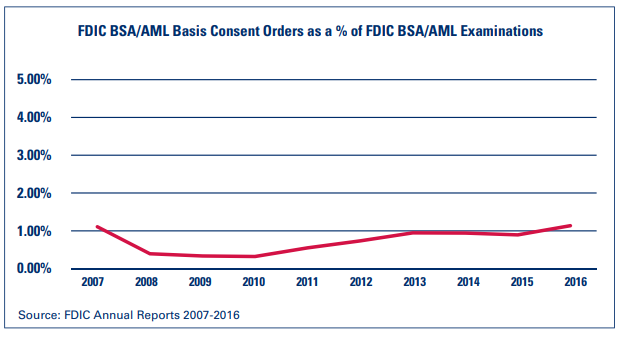

Compliance deficiencies often result in citations of apparent violations, but citations of violations do not necessarily result in the issuance of enforcement actions. During the past ten years, approximately one percent of examinations resulted in BSA/AML formal enforcement actions.

When Does the FDIC Use a Formal Enforcement Action to Address BSA Problems?

Pursuant to the Interagency Enforcement Guidance previously mentioned, the FDIC will issue a cease and desist order based on a violation of the requirement in Section 8(s) to establish and maintain a reasonably designed BSA compliance program where the institution:

- Fails to have a written BSA compliance program, including a CIP that adequately covers the required program components (i.e., internal controls, independent testing, designated compliance personnel, and training); or

- Fails to implement a BSA compliance program that adequately covers the required program components.

The FDIC will also issue a cease and desist order under Section 8(s) where the institution:

- Has defects in its BSA compliance program in one or more program components that indicate that either the written program or its implementation is not effective.

The following provides an example of where BSA compliance program defects, coupled with other aggregating factors, such as the potential for unreported money laundering activities, rendered the program ineffective thereby requiring a cease and desist order under Section 8(s).

Based on a review of relevant facts and circumstances, the FDIC also will issue a cease and desist order when an institution fails to correct a previously reported problem with its BSA compliance program. To be considered a problem within the meaning of Section 8(s), a deficiency would generally involve a serious defect in one or more of the required BSA compliance program components, and would have been identified in a report of examination or other written supervisory communication as requiring communication to the institution’s board of directors or senior management as a matter that must be corrected.

The FDIC does not ordinarily issue a cease and desist order under Section 8(s) unless the deficiencies identified during a subsequent examination or visitation are substantially the same as those previously reported to the institution. For example:

Certain problems with an institution’s BSA compliance program may not be fully correctable before the next examination or visit, such as when correction is addressed through implementing a new computer system. In these instances, a cease and desist order would not be issued if the institution had made substantial progress and acted in a timely fashion toward correcting the identified issues, provided the institution had adequate measures to comply with the BSA.

Conclusion

BSA compliance programs are integral elements in the AML/CFT framework as they aid in the prevention and detection of bad actors seeking to misuse the financial system. Depository institutions are required to establish a BSA compliance program commensurate with the risk profile of the institution. Most BSA compliance program deficiencies are corrected during the normal course of the supervisory process without the need for a formal enforcement action. When BSA compliance program deficiencies become problems, the FDIC provides recommendations to address the contributing factors through a variety of means before considering issuing a formal enforcement action.

The FDIC recognizes the challenges and costs associated with BSA compliance, especially as criminal organizations, terrorist financiers, and other illicit actors use creative and increasingly sophisticated methods to adapt to changes in the financial, technological, and regulatory landscape. The vast majority of FDIC- supervised institutions are successful in complying with the BSA, and play an important role in promoting public confidence and stability in the financial system.

Natalie Noyes

Review Examiner,

Division of Risk Management Supervision

nnoyes@fdic.gov

1 The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s Law Enforcement Awards ceremony, May 9, 2017.

2 For purposes of this article, the federal financial regulatory agencies are the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and National Credit Union Administration.

3 Gruenberg, Martin J. “Fostering Financial Integrity – The Role of Regulators, Industry, and Educators, Remarks” at Case Western University School of Law Financial Integrity Institute, March 23, 2017.

4 FinCEN was established in 1990 as an office within the Treasury Department to support law enforcement efforts and foster interagency and global cooperation against domestic and international financial crimes. In 1994, its mission was broadened to include regulatory responsibilities, and the Treasury Department’s precursor of FinCEN, the Office of Financial Enforcement was merged with FinCEN. On September 26, 2002, Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act was passed and included a provision to elevate FinCEN as an official bureau in the Department of the Treasury.

5 The majority of state bank regulatory agencies examine for BSA/AML compliance. The FDIC conducts BSA/ AML examinations for those states that do not conduct BSA/AML examinations; which averages less than 20 BSA/AML examinations annually on behalf of state counterparts.

6 Insured state nonmember institutions are state-chartered institutions that are not members of the Federal Reserve System. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency examines national banks for BSA/AML compliance, and the Federal Reserve conducts BSA/AML examinations for state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System. Federally insured credit unions are examined for BSA/AML compliance by the National Credit Union Administration.

7 31 CFR Chapter X.

8 12 CFR 326.8.

9 12 CFR 353.

10 12 USC 1818(s).

11 Financial Institution Letter FIL 71-2007 and the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council BSA/AML Examination Manual, Appendix R.