This regular feature focuses on topics of critical importance to bank accounting. Comments on this column and suggestions for future columns can be e-mailed to SupervisoryJournal@fdic.gov.

Effective internal control is a foundation for the safe and sound operation of a depository institution. The importance of internal control is recognized in Section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, the provisions of which the federal banking agencies have implemented through the issuance of Interagency Guidelines Establishing Standards for Safety and Soundness.1 These standards direct each institution to develop and implement an internal control system appropriate to its size and the nature, scope, and risk of its activities.

Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s board of directors, management, and other personnel. It is designed to provide reasonable assurance about the achievement of the institution’s objectives with regard to the reliability of financial reporting, the effectiveness and efficiency of operations, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. The design and formality of an entity’s internal control will vary depending on its size, the industry in which it operates, its culture, and management’s philosophy.2

Examiners perform an overall assessment of an institution’s system of internal control during each examination. In addition, although the federal banking agencies generally require only institutions with $500 million or more in total assets to have an annual audit of their financial statements, the agencies have long encouraged all institutions to have an external audit.3 In this regard, the Management component rating in the Uniform Financial Institutions Rating System specifically includes as an evaluation factor the adequacy of audits and internal control. Recent changes in the requirements governing external auditors’ communication of internal control deficiencies have made this information more readily accessible to examiners. As a result, an understanding of these changes will assist examiners in assessing the quality of an institution’s internal control environment and the actions management is taking to remedy any identified deficiencies. This article discusses internal control communication as a part of the audit process, summarizes the development of internal control standards, provides examples of control deficiencies, explains how these deficiencies should be evaluated and communicated by the auditor, and looks ahead to potential changes to authoritative guidance. As a starting point, we describe how this internal-control related information is used in the examination process.

The Role of Internal Control Information in the Examination Process

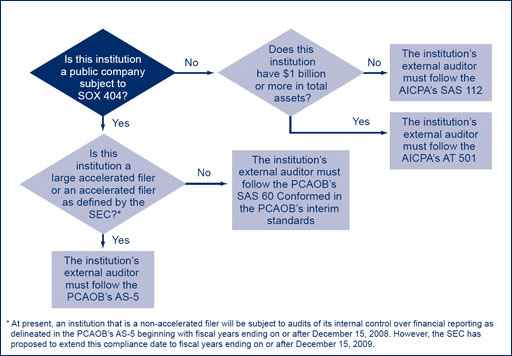

Subsequent sections of this report describe the evolution of, and recent changes to, professional standards governing an external auditor’s communication of internal control matters. These recent changes, particularly those mandating that communications be in writing, should improve an examiner’s ability to assess the quality of the internal control system at an institution that has undergone a financial statement audit or an internal control audit or attestation, either at the institution level or a consolidated parent company level. For such an institution, its total assets and whether it is a public company or a subsidiary of a public company (and, if so, whether the public company is an accelerated or non-accelerated filer) will dictate the types of written communication about internal control the external auditor should have provided to management and the audit committee. An examiner’s consideration of an institution’s internal control begins during pre-examination planning. Ideally, the examiner should obtain these written communications as part of this process. The examiner’s evaluation of the external auditor’s internal control communications should be an integral part of the planning activities and play a key role in the overall assessment of a bank’s internal control system.

An institution subject to Part 363 of the FDIC’s regulations is required to file copies of audit-related reports received from its external auditor with the appropriate FDIC regional or area office. These reports also must be filed with the district or regional office of its primary federal regulator, if other than the FDIC, and its appropriate state supervisor if it is state chartered. For example, if copies of these reports have not already been furnished to the FDIC examiner’s field office, copies should be obtained from the regional or area office. Depending on an institution’s size and whether it or its parent is a public company, internal control-related reports submitted pursuant to Part 363 would include the auditor’s report on the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting, either as part of the Part 363 annual report or separately; reports on significant deficiencies and material weaknesses; and reports on other internal control matters, which may be in the form of a management letter.4 If it appears that any internal control-related reports required to be filed under Part 363 have not been submitted, the examiner should ask management during the pre-examination planning process to provide a copy of the report to the examiner and to submit copies to the FDIC regional or area office and other appropriate federal and state supervisors. An institution’s failure to file an audit-related report with these offices in a timely manner represents an apparent violation of Part 363, which should be cited in the examination report.

In the case of an FDIC-supervised bank not subject to Part 363 whose financial statements are audited (or are included in its parent company’s audited consolidated financial statements), the FDIC has requested that the bank submit copies of its audit report and any other reports it receives from its external auditor, including any management letter, to the appropriate regional or area office and state supervisor.5 The reports prepared by the external auditor that an examiner should expect to see vary depending on whether the institution (or its parent company) is a public accelerated or non-accelerated filer or a nonpublic company. If audit-related reports are not available to the examiner at the beginning of the pre-examination planning process, the examiner should request copies of these reports from management.

Given the timely filing requirement for external auditors’ reports that applies to institutions subject to Part 363, existing policy guidance directs FDIC regional and area offices to review these filings after their receipt. In light of the long-standing request for FDIC-supervised banks not subject to Part 363 that undergo audits to submit these types of reports to the appropriate regional or area office, these reports also should be reviewed after receipt as part of an institution’s ongoing oversight and supervision. The purpose of promptly reviewing reports prepared by an institution’s external auditor is the early identification of the need for improvements in the institution’s financial management. If the review of these reports discloses control deficiencies that raise significant or immediate safety and soundness concerns about an institution, field supervisors should advance the examination date for the institution, schedule a visit, or initiate other appropriate follow-up with the institution. Reported control deficiencies of less immediate or significant concern should be flagged for consideration during the pre-examination planning process for the next examination.

An examiner’s preliminary assessment of risk areas during the pre-examination planning process considers the CAMELS (capital, asset quality, management, earnings, liquidity, and sensitivity to market risk) components, as well as such areas as internal control. The examiner determines the perceived risk in each risk area, as this will dictate whether greater-than-normal, normal, or less-than-normal examination resources will be devoted to the area. In general, sources of information include the bank’s previous examination reports and examination workpapers, correspondence files, and financial information and ratios. In the internal control area, the written communications from the external auditor described above and the results of previously conducted reviews of these documents should be evaluated. For institutions with $1 billion or more in total assets and those that are public companies (or subsidiaries of public companies), management’s report on its assessment of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting should also be obtained and evaluated. The examiner is also expected to contact the external auditor as part of the pre-examination planning, which enables the examiner to ask follow-up questions about the auditor’s written communications and inquire about and discuss any other recommendations that the auditor may have provided to management. Also relevant to the examiner’s effort to reach a conclusion on the level of perceived internal control risks within the bank is work performed by the internal audit function, as well as management’s responses to the control deficiencies, particularly any material weaknesses, identified by external or internal auditors or by management itself. Depending on the examiner’s conclusion regarding the perceived level of risk, if management and the external auditor have performed assessments of internal control over financial reporting, the examiner may determine that a better understanding of the bank’s internal control structure and procedures would be gained by reviewing the external auditor’s workpapers and the records maintained by management to support its internal control assertion.

During the examination, internal control deficiencies and other matters noted in the external auditor’s communications to management and the audit committee (or board of directors), as well as any deficiencies identified by the institution itself, and corrective actions taken by management should be reviewed and evaluated. The examiner should also consider the reasonableness of any decision by management not to remedy an identified deficiency based on management’s conscious acceptance of specific risk due to factors such as cost or the mitigating effect of compensating controls. If the examiner concludes that management’s actions are not adequate under the circumstances, the examiner should make recommendations for improvement. The deficiencies in internal control and management’s responses should be described in the report of examination on the Risk Management Assessment page or the Examination Conclusions and Comments page, depending on the level of significance of the deficiencies and management’s willingness or unwillingness to implement appropriate corrective actions. Discussion of these matters during any meeting with the institution’s board of directors to discuss the examination findings also may be warranted. The nature and severity of identified internal control deficiencies and management’s action or inaction to address these matters should be considered in the assignment of the Management component rating.

Audits of Financial Statements and Internal Control

An external auditor brings an independent and objective view to an institution’s financial reporting process. This, in turn, contributes directly to the achievement of the institution’s objectives for this process by performing a financial statement audit and, in some cases, an internal control audit or examination. Indirectly, this process provides information useful to management, the board of directors, and its audit committee in carrying out their responsibilities. The objective of an audit of an institution’s financial statements is for the external auditor to express an opinion on the fairness with which the financial statements present, in all material respects, the institution’s financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.6 The auditor’s opinion is communicated to the institution’s board of directors, audit committee, and management through the auditor’s report. When conducting a financial statement audit, the auditor must obtain a sufficient understanding of the institution’s internal control to plan the audit and determine the nature, timing, and extent of tests to be performed during the audit. Although the auditor may become aware of control deficiencies during the course of a financial statement audit, the auditor is not required to perform procedures for the specific purpose of identifying deficiencies in internal control. Nevertheless, among the responsibilities of the external auditor in connection with a financial statement audit is to communicate to management and the audit committee (or board of directors) matters related to the institution’s internal control over financial reporting that were identified during the audit. An external auditor may also be engaged to audit or examine the effectiveness of an institution’s internal control over financial reporting and express an opinion on it at the end of the fiscal year. In connection with such an engagement, the auditor also has a responsibility to communicate certain information concerning internal control matters to management and the audit committee.

During the financial statement audit and the internal control audit or examination, the auditor may discover deficiencies related to an institution’s internal control over financial reporting that should be reported to management and those charged with governance. Guidelines and professional standards related to the auditor’s communication of internal control deficiencies are continually evolving. Standards are established by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) for nonpublic company audits and attestation engagements and, since 2003, by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) for public company audits.

History of Internal Control Communications by External Auditors

Reporting on internal control matters is not a new development in the auditing profession. Table 1 presents a timeline of certain professional standards and laws and regulations pertinent to an external auditor’s communication of internal control matters.

Table 1

| An Auditor’s Required Communication of Internal Control Deficiencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Standard, Law, or Regulation | Required Communication | To Whom Communicated |

| August 1977 | AICPA SAS 20, “Required Communication of Material Weaknesses in Internal Accounting Control” (superseded by SAS 60) | Material weaknesses | Management and board of directors |

| July 1980 | AICPA SAS 30, “Reporting on Internal Accounting Control” (superseded by SSAE 2) | Report on the study and evaluation of the system of internal accounting control, including any material weaknesses | The entity being studied, its board of directors, or its stockholders |

| April 1988 | AICPA SAS 60 “Communication of Internal Control Structure Related Matters Noted in an Audit” (superseded by SAS 112) | Reportable conditions and material weaknesses, preferably in writing | Audit committee (or those with equivalent authority and responsibility) |

| May 1993 | AICPA SSAE 2, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Structure Over Financial Reporting” (codified as AT501) (superseded by SSAE 10) | Attestation report on management’s assertion about the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting; reportable conditions and material weaknesses, preferably in writing | Audit committee (or those with equivalent authority and responsibility) |

| June 1993 | FDIC Part 363, “Annual Independent Audits and Reporting Requirements” (amended November 2005) | For insured institutions with $500 million or more in total assets, requires an auditor’s attestation report on management’s internal control assessment report | Audit committee, FDIC, other appropriate federal and state depository institution supervisors, and the public in the Part 363 annual report |

| January 2001 | AICPA SSAE 10, “Attestation Standards: Revision and Recodification”: Chapter 5, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting” (codified as AT 501) | Report on management’s assertion about the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting; reportable conditions and material weaknesses, preferably in writing | Management and “those charged with governance” (audit committee and/or board of directors) |

| July 2002 | Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Section 404, “Management Assessment of Internal Controls” | For public companies, requires an annual auditor’s attestation report on management’s assessment of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting | Public in Form 10-K annual report |

| March 2004 (approval by SEC in June 2004) | PCAOB AS-2, “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Performed in Conjunction With an Audit of Financial Statements” (superseded by AS-5) | Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses. Requires an auditor’s attestation report on management’s internal control assessment report and an audit report on internal control over financial reporting to be filed with the annual report | Management and audit committee; material weaknesses disclosed to public in Form 10-K annual report |

| September 2004 (approval by SEC in November 2004) | Amendments to SAS 60 in PCAOB’s interim standards to bring them into conformity with AS2 | Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified in an audit only of financial statements | Management and audit committee |

| November 2005 | Amendments to FDIC Part 363, “Annual Independent Audits and Reporting Requirements” | Raised the asset-size threshold for the auditor’s report on the assessment of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting from $500 million to $1 billion | See Part 363 above (June 1993) |

| May 2006 | AICPA SAS 112, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit” | Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses | Management and “those charged with governance” (audit committee and/or board of directors) |

| August 2006 | Amendments to AICPA AT 501 “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting” | Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses | Management and “those charged with governance” (audit committee and/or board of directors) |

| May 2007 (approval by SEC in July 2007) | PCAOB AS-5, “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated With An Audit of Financial Statements” | Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses. Requires an auditor’s report on the audit of internal control over financial reporting to be filed with the annual report | Management and audit committee; material weaknesses disclosed to public in Form 10-K annual report |

Standards for Auditors of Nonpublic Companies

All companies not subject to the registration or periodic reporting requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 are considered nonpublic companies. The AICPA’s standards applicable to the preparation and issuance of audit and attestation reports for nonpublic companies include Statements on Auditing Standards (SASs) and Statements on Standards for Attestation Engagements (SSAEs).

SASs are issued by the Auditing Standards Board (ASB), the senior technical body of the AICPA designated to issue pronouncements on auditing, attestation, and quality control matters applicable to the performance and issuance of audit and attestation reports for nonpublic companies. In 1972, all previous Statements on Auditing Procedures (SAP No. 33 to SAP No. 54) were codified into SAS 1, ushering in the modern era of professional auditing standards. In August 1977, SAS 20, “Required Communication of Material Weaknesses in Internal Accounting Control,” was issued and introduced the concept of a “material weakness.” In April 1988, SAS 20 was superseded by SAS 60, “Communication of Internal Control Structure Related Matters Noted in an Audit,” to introduce the concept of a “reportable condition.”

In May 2006, the ASB issued SAS 112, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” superseding SAS 60. SAS 112 applies to audits of nonpublic companies. Although SAS 60 is no longer applicable to audits of nonpublic companies, an amended version issued by the PCAOB remains applicable to audits of public companies, as detailed below. SAS 112 establishes standards and provides guidance on communicating matters related to an institution’s internal control over financial reporting identified in an audit of financial statements. Specifically, SAS 112

- Defines the terms “control deficiency,” “significant deficiency,” and “material weakness”;

- Replaces the term “reportable condition,” which had been included in SAS 60;

- Provides guidance on evaluating the severity of control deficiencies identified in an audit of financial statements;

- Identifies areas in which control deficiencies ordinarily are to be evaluated as at least significant deficiencies in internal control, as well as indicators of control deficiencies that should be regarded as at least a significant deficiency and a strong indicator of a material weakness in internal control; and

- Requires the auditor to communicate, in writing, to management and those charged with governance, significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified in an audit.

SAS 112 is applicable whenever an auditor expresses an opinion on financial statements (including a disclaimer of opinion) of a nonpublic entity. SAS 112 took effect for audits of financial statements of nonpublic companies for periods ending on or after December 15, 2006. Thus, for institutions with calendar year fiscal years, this auditing standard first applied to year-end 2006 audits. SAS 112 is codified in the AICPA’s Professional Standards as AU Section 325.7

SSAEs also are issued by the AICPA’s ASB. Attestation standards apply only to attest services other than a financial statement audit rendered by a certified public accountant in the practice of public accounting. Attestation standards do not override the requirements of any existing SAS. At present, the attestation standard specifically addressing communication of internal control matters is Chapter 5, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting,” of SSAE No. 10, “Attestation Standards: Revision and Recodification.” Chapter 5 is codified in the AICPA’s Professional Standards as AT Section 501 (AT 501). AT 501 was effective for internal control attestations on or after June 1, 2001. As its title indicates, SSAE No. 10 superseded the then-existing attestation standards, including the predecessor to Chapter 5, SSAE No. 2, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Structure Over Financial Reporting,” which was issued in May 1993 largely in response to the enactment of Section 36 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act as part of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991. As shown in Table 1, SSAE No. 2 superseded an earlier SAS.

In August 2006, the ASB amended AT 501 to incorporate the new terms, related definitions, and guidance on identifying and evaluating control deficiencies and communicating significant deficiencies and material weaknesses that were introduced by the issuance of SAS 112. Thus, the changes the ASB made to AT 501 were the same as those made in replacing SAS 60 with SAS 112, as discussed above. In addition, the ASB revised the illustrative internal control attestation reports in AT 501 to be consistent with SAS 112. The effective date of these conforming changes to AT 501 corresponds to that of SAS 112, that is, for internal control attestations as of or for a period ending on or after December 15, 2006.8

Standards for Auditors of Public Companies

A public company is any company that has a class of securities registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or the appropriate banking agency under Section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the Act) or that is required to file reports with the SEC under Section 15(d) of the Act. The SEC, in Rule 12b-2 of the Act, divides public companies into three categories: large accelerated filers, accelerated filers, and non-accelerated filers. In general, large accelerated filers are public companies whose voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates has an aggregate market value of $700 million or more. Accelerated filers are public companies whose voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates has an aggregate market value of between $75 million and $700 million, and non-accelerated filers are public companies whose voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates has an aggregate market value of less than $75 million.

In July 2002, Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), Section 404 of which established new provisions related to internal control over financial reporting for public companies. Section 404 requires a public company’s management to assess and report on the effectiveness of the company’s internal control over financial reporting and the company’s external auditor to examine the effectiveness of, and attest to management’s assessment of, this internal control structure. SOX also created the PCAOB, a private-sector non-profit corporation, to oversee the external auditors of public companies as a means of protecting the interests of investors and further the public interest in the preparation of informative, fair, and independent audit reports.9 The PCAOB is authorized to establish auditing and related attestation, quality control, ethics, and independence standards and rules to be followed by public company auditors in the preparation and issuance of audit reports. Furthermore, auditors of public entities are required to register with the PCAOB, which conducts an inspection program to assess these auditors’ compliance with federal securities laws and regulations, the PCAOB’s rules, and professional standards in connection with their audits of public companies.

Although the ASB no longer has the authority to establish standards for audits of public companies, on April 16, 2003, the PCAOB adopted the AICPA’s then-existing auditing and attestation standards as its interim standards. Public company auditors must comply with these interim standards to the extent they have not been superseded or amended by the PCAOB. The interim standards originally included SAS 60 and AT 501 in the form in which they existed on April 16, 2003, and had been codified in the AICPA’s professional standards. In March 2004, the PCAOB issued Auditing Standard No. 2 (AS-2), “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Performed in Conjunction With an Audit of Financial Statements.” Among the key elements of AS-2 is a requirement that the auditor communicate in writing to a public company’s management and its audit committee all significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified during the audit. AS-2 superseded the AT 501 interim standard for public companies.

The auditors of all accelerated filers were required to implement the provisions of AS-2 in an integrated audit of financial statements and internal control over financial reporting for fiscal years ending on or after November 15, 2004. However, non-accelerated filers have not yet been required to undergo an audit of internal control over financial reporting when their financial statements are audited. As a consequence, in September 2004, the PCAOB adopted conforming amendments to its interim standards resulting from its adoption of AS-2. These amendments revised SAS 60 in the interim standards to require the auditor of a non-accelerated filer to report to management and the audit committee only those control deficiencies identified in the audit of the financial statements that are either significant deficiencies or material weaknesses, which is similar to the AS-2 communication requirement.10 The PCAOB‘s conforming amendments to SAS 60 became effective for audits of financial statements for periods ending on or after July 15, 2005.

After its adoption of AS-2, the PCAOB monitored how auditors had implemented the requirements of this auditing standard. The PCAOB determined that audits of internal control over financial reporting provided significant benefits, particularly in terms of corporate governance and quality of financial reporting; however, these benefits had come at a significant cost. The PCAOB observed that the costs were often higher than anticipated and the related effort in some cases has appeared greater than necessary to conduct an effective audit of internal control over financial reporting.11 In May 2007, after considering public comments received and input from the SEC, the PCAOB decided to replace AS-2 with a revised standard on auditing internal control, Auditing Standard No. 5, “An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated With An Audit of Financial Statements” (AS-5). AS-5 is effective for internal control audits of public entities for fiscal years ending on or after November 15, 2007, with earlier adoption permitted after July 25, 2007, the date of the SEC’s approval of AS-5. The PCAOB’s intent in adopting AS-5 was to focus the internal control audit on the areas of greatest risk, eliminate unnecessary procedures, scale the internal control audit to a public company’s size and complexity, and simplify the text of the standard compared with AS-2.12 AS-5 also revised the definitions of material weakness and significant deficiency (see “Communication of Significant Deficiencies and Material Weaknesses” later in this article). Because of these definitional changes, the PCAOB also adopted additional conforming amendments to the version of SAS 60 in its interim standards (“SAS 60 Conformed”).

Insured Depository Institutions

For insured depository institutions with $500 million or more in total assets, the annual audit and reporting requirements in Part 363 of the FDIC’s regulations include provisions that address the external auditor’s communications about and reporting on the internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting. Since Part 363 was initially adopted by the FDIC in 1993, Section 363.4(c) has required each insured institution to file a copy of any management letter or other audit-related report issued by its external auditors within 15 days after receipt with the FDIC, the appropriate federal banking agency, and any appropriate state bank supervisor. Institutions with at least $500 million but less than $1 billion in total assets that are also public companies or subsidiaries of public companies subject to the provisions of Section 404 of SOX for the most recent fiscal year must also file their auditor’s report on the audit of internal control over financial reporting as an “other report.” All institutions with $1 billion or more in total assets, both public and nonpublic, are required to submit the external auditor’s audit or attestation report concerning the institution’s internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting as part of the Part 363 annual report.13

Chart 1: External Auditors’ Communication on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting for Insured Depository Institutions

Definitions

In evaluating an institution’s internal control environment, following the correct standard is critical, as previously discussed. Moreover, each standard defines key terms linked to the standard’s communication requirements. The definitions in these standards have similarities and differences that should be noted to ensure the appropriate level of auditor evaluation and communication.

Professional Definition | SAS 112 and AT 501 14,15 | AS-5 and SAS 60 Conformed 16,17 |

|---|---|---|

| Control Deficiency | A control deficiency exists when the design or operation of a control does not allow management or employees, in the normal course of performing their assigned functions, to prevent or detect financial statement misstatements on a timely basis. | |

| Control Deficiency: Deficiency in Operation | A deficiency in operation exists when a properly designed control does not operate as designed or when the person performing the control does not possess the necessary authority or qualifications to perform the control effectively. | |

| Control Deficiency: Deficiency in Design | A deficiency in design exists when (a) a control necessary to meet the control objective is missing or (b) an existing control is not properly designed so that even if the control operates as designed, the control objective is not always met. | A deficiency in design exists when (a) a control necessary to meet the control objective is missing or (b) an existing control is not properly designed so that even if the control operates as designed, the control objective would not be met. |

| Significant Deficiency | A significant deficiency is a control deficiency, or combination of control deficiencies, that adversely affects the institution’s ability to initiate, authorize, record, process, or report financial data reliably in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles such that there is more than a remote likelihood that a misstatement of the institution’s financial statements that is more than inconsequential18 will not be prevented or detected. | A significant deficiency is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting that is less severe than a material weakness, yet important enough to merit attention by those responsible for oversight of the company’s financial reporting. |

| Material Weakness | A material weakness is a significant deficiency, or combination of significant deficiencies, that results in more than a remote likelihood that a material misstatement of the financial statements will not be prevented or detected. | A material weakness is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the company’s annual or interim financial statements will not be prevented or detected on a timely basis. |

A material weakness, as defined in the context of SAS 112 and AT 501, adopts the standard of “more than a remote likelihood” that a material misstatement of the financial statements will not be prevented or detected. By contrast, AS-5 and SAS 60 Conformed characterize a material weakness as a deficiency or combination of deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting such that there is a “reasonable possibility” that a material misstatement will not be prevented or detected. Both a “reasonable possibility” and “more than a remote likelihood” of an event, as used in these standards, occur when the likelihood of the event is either “reasonably possible” or “probable,” as those terms are used in Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 5, “Accounting for Contingencies” (FAS 5). According to FAS 5, a contingency is an existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain or loss that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur. When a loss contingency exists, the likelihood that the future event or events will confirm the loss can range from “probable” to “remote.”19 “Probable” means that the future event or events are likely to occur, and “reasonably possible” means that the chance of the future event or events occurring is more than remote but less than likely.20 In addition, FAS 5 uses the term “remote” to mean that the chance of the future event or events occurring is slight.

Internal Control Deficiencies Under SAS 112

| Examples of Circumstances That May Be Control Deficiencies, Significant Deficiencies, or Material Weaknesses Under SAS 112 21 | |

|---|---|

| Deficiencies in the Design of Controls | |

| |

| Failures in the Operation of Internal Control | |

| |

Evaluating Control Deficiencies Identified as Part of a Financial Statement Audit

In evaluating identified control deficiencies, the auditor should consider the likelihood and magnitude of misstatement of the financial statements as well as the effect of compensating controls. The significance of a control deficiency depends on the potential for a misstatement, not on whether a misstatement actually has occurred. In this regard, the absence of an identified misstatement does not provide evidence that identified control deficiencies are not significant deficiencies or material weaknesses.22

| Examples of Factors Influencing Whether a Control Could Fail to Prevent or Detect a Financial Statement Misstatement 23 | |

|---|---|

| |

When multiple control deficiencies affect the same financial statement account balance or disclosure, the combination of these deficiencies may constitute a significant deficiency or material weakness, even though the deficiencies are individually insignificant. Factors affecting the magnitude of a financial statement misstatement resulting from a control deficiency or combination of deficiencies include, but are not limited to, the following:

- The financial statement amounts or total of transactions exposed to the deficiency. (The maximum amount of an overstatement is generally the recorded amount, but not for an understatement because of the potential for unrecorded amounts.)

- The volume of activity in the account balance or class of transactions exposed to the deficiency in the current period or expected in future periods.

| Deficiencies in the Following Areas Ordinarily Are at Least Significant Deficiencies in Internal Control 24 | |

|---|---|

| |

A compensating control is a control that limits the severity of a deficiency in another control and thereby prevents that other control from becoming a significant deficiency or a material weakness. Therefore, when evaluating whether a control deficiency or a combination of deficiencies is a significant deficiency or a material weakness, an auditor should evaluate the possible mitigating influence of compensating controls found to be effective. However, even if the compensating controls prevent a control deficiency from rising to the level of a significant deficiency or a material weakness, they do not eliminate the control deficiency.

| Deficiencies in the Following Areas Should Be Regarded as at Least a Significant Deficiency and a Strong Indicator of a Material Weakness in Internal Control 25 | |

|---|---|

| |

Communication of Significant Deficiencies and Material Weaknesses

When conducting an audit, the auditor follows the appropriate professional standard as described above. When the auditor discovers control deficiencies, the same professional standards provide guidance about the level and form of communication required to be presented to the institution’s board of directors or the audit committee.

SAS 112

Whenever an auditor audits the financial statements of a nonpublic institution and identifies control deficiencies, SAS 112 requires the auditor to communicate significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in writing to management and the board of directors or its audit committee. The standard states that this written communication is best made by the report release date, but must be made no later than 60 days following the report release date. The report release date is the date the auditor grants the institution permission to use the auditor’s audit report (opinion) in connection with the financial statements, which is typically the date the auditor delivers the audit report to the institution. Significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified during the audit, regardless of any conscious decision by management to accept that degree of risk, must be communicated to management and the board and/or audit committee as a part of each audit. This communication includes any significant deficiencies and material weaknesses communicated in previous audits that remain unremediated. The auditor may communicate in writing concerning unremediated deficiencies and weaknesses by referring to the previously issued written communication and the date of that communication.26

The auditor’s written communication regarding significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified during an audit of financial statements should state that the purpose of the audit was to express an opinion on the financial statements, but not to express an opinion on the effectiveness of the institution’s internal control over financial reporting. The auditor should also state that the auditor is not expressing an opinion on internal control effectiveness. The written communication should include the definitions of the terms “significant deficiency” and, where relevant, “material weakness,” and it should identify the matters considered to be significant deficiencies and, if applicable, material weaknesses.27

If no material weaknesses were identified during an audit of a nonpublic institution’s financial statements, the auditor may, at the institution’s request, issue a written communication advising management and the board of directors or its audit committee of this fact. However, the auditor should add a statement to the written communication disclaiming an opinion on the effectiveness of the institution’s internal control. In contrast, the auditor should not issue a written communication stating that no significant deficiencies were identified during the audit, because of the potential for the limited degree of assurance provided by such a communication to be misinterpreted. If the auditor has performed an examination of internal control over financial reporting under the provisions of AT 501 for the same period or “as of” date as the audit of the financial statements, the auditor should not issue a report indicating that no material weaknesses were identified during the audit of the financial statements.28

AT 501

AT 501 is not applicable when an auditor performs only an audit of a nonpublic institution’s financial statements. Rather, SAS 112 applies to such an audit. Under AT 501, an auditor engaged to examine the effectiveness of a nonpublic institution’s internal control over financial reporting reports directly on the effectiveness of the institution’s internal control or on management’s written assertion about the effectiveness of the institution’s internal control. The latter type of auditor’s report is currently required for internal control attestations for nonpublic institutions with $1 billion or more in total assets conducted under AT 501. The auditor also is required to communicate significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in writing to management and the board of directors or the audit committee. Unless a significant deficiency or material weakness is of such significance that an interim communication would be warranted, the auditor’s written communication takes place after the examination is concluded.29

AS-5

When an auditor performs an audit of a public institution’s internal control over financial reporting that is integrated with the audit of the financial statements, AS-5 requires the auditor to communicate material weaknesses in writing to management and the audit committee. This should occur prior to the issuance of the auditor’s report on internal control over financial reporting. An “integrated audit” is required for public institutions that are either large accelerated filers or accelerated filers as defined by the SEC. Significant deficiencies must also be communicated in writing to the audit committee; however, AS-5 does not specify when such communication should be made. If there are control deficiencies that, individually or in combination, result in one or more material weaknesses, the auditor must express an adverse opinion on the institution’s internal control over financial reporting, unless there is a restriction on the scope of the engagement. The auditor should also determine the effect that the adverse opinion on internal control has on the auditor’s opinion on the financial statements. In addition, the auditor should disclose whether the auditor’s opinion on the financial statements was affected by the adverse opinion on internal control over financial reporting.30

SAS 60 Conformed

In an audit of a public institution’s financial statements without an integrated internal control audit, SAS 60 Conformed requires the auditor to communicate in writing to management and the audit committee all significant deficiencies and material weaknesses identified during the audit. Currently, only nonaccelerated filers as defined by the SEC are allowed to undergo financial statement audits without an integrated internal control audit. The auditor’s written internal control communication should be made before the issuance of the auditor’s report on the financial statements. The auditor’s communication should distinguish clearly between those matters considered significant deficiencies and those considered material weaknesses.31

Other Communication of Internal Control Deficiencies

During the course of an audit, the auditor may discover internal control deficiencies that do not rise to the level of significant deficiencies or material weaknesses. These should be communicated to institution management in compliance with professional standards.

AS-5

During the course of an audit of a public institution’s internal control over financial reporting that is integrated with the audit of its financial statements, the auditor may identify deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting that are of a lesser magnitude than material weaknesses. The auditor should communicate to management, in writing, all such deficiencies and inform the audit committee when such a communication has been made. (Some of these deficiencies may be significant deficiencies about which the auditor must communicate in writing to the audit committee, as mentioned above.) When making this communication to management, it is not necessary for the auditor to repeat information about such deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting if they have been included in previously issued written communications, whether those communications were made by the auditor, internal auditors, or others within the institution. Furthermore, the auditor is not required to perform audit procedures sufficient to identify all control deficiencies; rather, the auditor should communicate deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting of which the auditor is aware. However, because the audit of internal control over financial reporting does not provide the auditor with assurance that he has identified all deficiencies less severe than a material weakness, the auditor should not issue a report stating that no such deficiencies were noted during the audit.32

As a separate matter, if the auditor concludes that the oversight of the institution’s external financial reporting and internal control over financial reporting by the institution’s audit committee is ineffective, the auditor must communicate that conclusion in writing to the board of directors.33

SAS 60 Conformed

During an audit of the financial statements of a public institution when an audit of internal control over financial reporting is not required to be conducted, the auditor may identify matters in addition to those required to be communicated by SAS 60 Conformed. These matters include control deficiencies that are neither significant deficiencies nor material weaknesses, and are matters the institution may request the auditor be alert to that go beyond those contemplated by SAS 60 Conformed. The auditor may report such matters to management, the audit committee, or others, as appropriate, although the communication is not required to be in writing. However, if the auditor did not identify any significant deficiencies during the audit of the financial statements, the auditor should not report in writing that no such deficiencies were discovered because of the potential for the limited degree of assurance associated with such a report to be misinterpreted. When timely communication of internal control deficiencies is important, the auditor should communicate such deficiencies during the audit rather than at the end of the engagement. The decision about whether to issue an interim communication should be based on the relative significance of the matters noted and the urgency of corrective follow-up action required.34

SAS 60 Conformed does not explicitly require the auditor to evaluate the effectiveness of the audit committee’s oversight in an audit of only the financial statements. However, if the auditor becomes aware that the audit committee’s oversight of the institution’s external financial reporting and internal control over financial reporting is ineffective, the auditor must communicate that information in writing to the board of directors. Such ineffective oversight should be regarded as an indicator that a material weakness in internal control over financial reporting exists.35

SAS 112

When an auditor performs a financial statement audit for a nonpublic institution, the auditor may communicate, either orally or in writing, to management and the board of directors or its audit committee, other matters that the auditor believes to be of potential benefit to the institution, such as recommendations for operational or administrative efficiency or for improving internal control. In addition, the auditor should report on any matters requested by the institution, such as control deficiencies that are not significant deficiencies or material weaknesses.

What Does the Future Hold?

As discussed in this article, the AICPA modified its attestation standards in AT 501 and replaced its auditing standards in SAS 60 with SAS 112 to conform its professional standards to the terminology and communication requirements of the PCAOB’s AS-2. AT 501 was in the process of a more comprehensive revision in early 2006, but the AICPA delayed this initiative when the PCAOB announced in May 2006 that it would undertake an initiative to amend AS-2. The PCAOB later decided against amending AS-2 and elected instead to replace AS-2 with a new auditing standard, which became AS-5. As a result, the definitions of certain internal control-related terms and auditors’ communication standards currently differ somewhat for audits of public companies and nonpublic companies. Changes to SAS 112 and AT 501 to bring these standards more in line with those of the PCAOB are the purview of the AICPA’s ASB. Although the PCAOB adopted AS-5 in May 2007, the ASB is waiting to see what changes the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board will make to the International Standards on Auditing on auditor communication as part of its “Clarity” project.

The PCAOB also is continuing to develop for auditors of smaller public companies guidance for applying AS-5 and is continuing to hold Forums on Auditing in the Small Business Environment to better monitor implementation issues related to smaller public companies.36

In October 2007, the FDIC Board of Directors approved the publication of proposed amendments to Part 363 of the FDIC’s regulations that would, among other things, address communications between an institution’s external auditor and the audit committee. These reporting requirements are intended to strengthen the relationship between the audit committee and the external auditor. The FDIC previously stated that effective communication between the external auditor who audits the institution’s financial statements and the institution’s audit committee assists the committee in carrying out its responsibilities. For this reason, the FDIC has encouraged institutions, regardless of whether they are public companies, to arrange with their external auditor to institute these reporting practices. One of the proposed amendments to Part 363 would establish a uniform minimum requirement for external auditor communications with the audit committees of both public and nonpublic institutions subject to this regulation. As proposed, the external auditor would be required to report on a timely basis to the audit committee about other written communications the auditor has provided to management, such as a management letter or schedule of unadjusted differences.37

As a result of these changes, the auditing profession and communications of internal control deficiencies identified in an audit are continuing to evolve. Overall, these changes are positive and are making information generated during audits about such deficiencies more readily available to examiners as they plan and conduct examinations.

Gregory B. Duncan

Policy Analyst

Division of Supervision and

Consumer Protection

GrDuncan@fdic.gov

1 Appendix A to Part 364 of the FDIC’s regulations.

2 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 3.

3 See the Interagency Policy Statement on External Auditing Programs of Banks and Savings Associations (FIL-96-99, October 25, 1999, https://archive.fdic.gov/view/fdic/5266).

4 The Part 363 Annual Report also includes audited comparative financial statements, a statement of management’s responsibilities, an assessment by management of compliance during the year with laws and regulations on insider lending and dividend restrictions, and, for institutions with $1 billion or more in total assets, management’s assessment of the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting as of year-end.

5 FIL-96-99, October 25, 1999.

6 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 110, “Responsibilities and Functions of the Independent Auditor,” November 1972, paragraph 1.

7 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” May 2007, p. 431.

8 AICPA Professional Standards, AT Section 501, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting,” AT 501, May 2007, pp. 2709–2732.

9 PCAOB Mission Statement, https://pcaobus.org/about/mission-vision-values.

10 PCAOB Conforming Amendments, Release No. 2004-008, September 15, 2004, p. 7.

11 PCAOB Proposed Auditing Standard: An Audit of Internal Control Over Financial Reporting That Is Integrated With An Audit of Financial Statements and Related Other Proposals, PCAOB Release No. 2006-007 (December 19, 2006).

12 PCAOB News Release, “Board Approves New Audit Standard for Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and, Separately, Recommendations on Inspection Frequency Rule,” May 24, 2007.

13 Financial Institution Letters FIL-119-2005, Annual Independent Audits and Reporting Requirements Amendments to Part 363.

14 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraphs 5–8.

15 AICPA Professional Standards, AT Section 501, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting,” paragraphs 36–40.

16 PCAOB Standards, AS-5, August 6, 2007, paragraphs A3, A7, A11.

17 PCAOB Conforming Amendments, August 6, 2007, Release 2007-005A, pp. 482–484.

18 For the SAS 112 definition of significant deficiency, the phrase “more than inconsequential” describes the magnitude of a potential misstatement that could occur as a result of a significant deficiency and is the threshold for evaluating whether a control deficiency or a combination of such deficiencies is a significant deficiency. In making this evaluation, the auditor determines whether a reasonable person would conclude, after considering the possibility of further undetected misstatements, that the misstatement, either individually or when aggregated with other misstatements, would clearly be material to the financial statements. The auditor should consider both qualitative and quantitative factors when determining whether a potential misstatement would be more than inconsequential.

19 Financial Accounting Standards Board, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 5, “Accounting for Contingencies,” paragraph 1.

20 Financial Accounting Standards Board, Statement on Financial Accounting Standards No. 5, “Accounting for Contingencies,” paragraph 3.

21 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 32.

22 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraphs 9 and 10.

23 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 11.

24 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 18.

25 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 19.

26 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraphs 20 and 21, and AU Section 339, “Audit Documentation,” footnote 6.

27 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 25.

28 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraphs 28 and 29.

29 AICPA Professional Standards, AT Section 501, “Reporting on an Entity’s Internal Control Over Financial Reporting,” paragraphs 49 and 50.

30 PCAOB Standards, AS-5, August 6, 2007, paragraphs 78, 80, 90, and 92.

31 AICPA Professional Standards, AU Section 325, “Communicating Internal Control Related Matters Identified in an Audit,” paragraph 4.

32 PCAOB Standards, AS-5, August 6, 2007, paragraphs 81–83.

33 PCAOB Standards, AS-5, August 6, 2007, paragraph 79.

34 PCAOB Conforming Amendments, Release 2004-008, September 15, 2004, pp. A-12–A-16.

35 PCAOB Conforming Amendments, August 6, 2007, Release 2007-005A, p. 483.

36 PCAOB News Release, “Board Approves New Audit Standard for Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and, Separately, Recommendations on Inspection Frequency Rule,” May 24, 2007.

37 Federal Register, Vol. 72, No. 212, Part II, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 12 CFR Parts 308 and 363, “Annual Independent Audits and Reporting Requirements; Proposed Rule,” November 2, 2007, pp. 62310–62335, https://www.fdic.gov/resources/regulations/federal-register-publications/2007/07proposenov2.pdf.