During much of this decade, the U.S. banking industry posted record earnings, attributable, at least in part, to strong growth in commercial real estate (CRE) lending. This expansion included a considerable increase in land acquisition, development, and construction (ADC) lending. This loan segment almost tripled, from $231 billion to more than $600 billion, and grew from 9 percent to 13 percent of total real estate loans from 2001 to 2007.1 Delinquency rates for the ADC portfolio were historically low during much of this time. However, credit quality began to show signs of weakening in 2006 as the level of noncurrent ADC loans began to rise. By year-end 2007, noncurrent loans had reached 3.15 percent—the highest level in more than 10 years—and more than triple the rate for other commercial real estate loans.2

In response to concern about a downturn in the housing market and potential effects on construction and development lending, the FDIC issued a Financial Institution Letter (FIL), Managing Commercial Real Estate Concentrations in a Challenging Environment, on March 17, 2008, that reemphasized the importance of robust credit risk management practices. Among other things, this FIL noted examiner observations of underwriting weaknesses in ADC loan portfolios where lenders added extra interest reserves when the underlying real estate project was not performing as expected. This practice can mask loans that would otherwise be reported as delinquent and erode collateral protection, increasing a lender’s exposure to credit losses.3 Examiners have observed instances where ADC loans with interest reserves make up a substantial proportion, or even a multiple, of bank capital.

This article focuses on the use of interest reserves in ADC lending, examines the risks this underwriting practice presents, and reviews regulatory guidance on the use of interest reserves. Finally, the article identifies “red flags” that should alert lenders to potential problems at each stage of the ADC cycle and reinforces the importance of evaluating the appropriateness of interest reserves when ADC projects become troubled.

The Use of Interest Reserves

For most lenders, the decision to establish a loan-funded interest reserve upon origination of an ADC loan is appropriately based on the feasibility of the project, the creditworthiness of the borrower and guarantors, and the protection provided by the real estate and other collateral.

The interest reserve account allows a lender to periodically advance loan funds to pay interest charges on the outstanding balance of the loan. The interest is capitalized and added to the loan balance. Frequently, ADC loan budgets will include an interest reserve to carry the project from origination to completion and may cover the project’s anticipated sell-out or lease-up period.

The calculation of the interest reserve depends on the size and complexity of the ADC loan. The amount of the interest reserve is generally calculated by multiplying the average outstanding balance of the loan by the interest rate and the length of the expected development/construction period. In those instances when an ADC loan has an adjustable interest rate, the lender factors the potential for rate changes into the interest reserve calculation.

Some lenders require the borrower to pay interest as an out-of-pocket expense or may require the borrower to establish a borrower-funded interest reserve to ensure payment.4 When applied appropriately, an interest reserve can benefit both the lender and the borrower. For the lender, an interest reserve provides an effective means for addressing the cash flow characteristics of a properly underwritten ADC loan. Similarly, for the borrower, interest reserves provide the funds to service the debt until the property is developed, and cash flow is generated from the sale or lease of the developed property.

Risks in the Use of Interest Reserves

Although potentially beneficial to the lender and the borrower, the use of interest reserves carries certain risks. Of particular concern is the possibility that an interest reserve could mask problems with a borrower’s willingness and ability to repay the debt consistent with the terms and conditions of the loan obligation. For example, a project that is not completed in a timely manner or falters once completed may appear to perform if the interest reserve keeps the troubled loan current. This is a much different scenario from most credit transactions in which cash flow problems are eventually reflected in late or past-due payments and sometimes even in nonpayment. A loan with a bank-funded interest reserve would not exhibit these warning signs.

With little potential for monetary default during the interest reserve period, some lenders may delay recognizing and evaluating the financial risks in a troubled ADC loan. In some cases, lenders may extend, renew, or restructure the term of certain ADC loans, providing additional interest reserves to keep the credit facility current. As a result, the true financial condition of the project may not be apparent and developing problems may not be addressed in a timely manner. Consequently, a bank may end up with a matured ADC loan where the interest reserve has been fully advanced, and the borrower’s financial condition has deteriorated. In addition, the project may not be complete, its sale or lease-up may not be sufficient to ensure timely repayment of the debt, or the value of the collateral may have declined, exposing the lender to increasing credit losses.

Some lenders also have used interest reserves on loans where interest and possibly principal should be paid by the borrower, given the nature and purpose of the loan. For example, the use of interest reserves in the following situations may not be appropriate and, as such, could heighten the lender’s vulnerability to credit losses:

- Loans on projects that have experienced development or construction delays, cost overruns, sales or leasing shortages, or are otherwise not performing according to the original loan agreement and have inadequate collateral support;

- Loans used to purchase real estate with no immediate or defined plans for development or construction;

- Conversion and rehabilitation loans or renewals with no immediate plans for construction, rehabilitation, or development; and

- Loans secured by income-producing rental properties (residential or commercial) that should be amortizing.

Overall, the use of interest reserves without prudent underwriting and loan portfolio risk management practices could heighten an insured financial institution’s risk profile and exacerbate loan losses, especially during times of economic stress.

Regulatory and Accounting Guidance

Beginning in 1985, the federal banking regulatory agencies issued guidance that addressed the use of interest reserves in the broader context of real estate lending standards and CRE concentrations.

- The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) issued an Examining Circular in May 1985 describing OCC policies governing the accounting treatment for capitalization of interest on loans.5 This circular states that even though regulatory and generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) do not provide specific guidance as to when it is appropriate to recognize interest income from an interest reserve, in practice it should be based on sound lending policies, prudent credit judgment, and a thorough evaluation of the creditworthiness of the borrower.

- The Interagency Guidelines for Real Estate Lending Policies, issued in 1992, establish the core underwriting and risk management practices for all extensions of credit secured by real estate.6 One provision addresses the need for an institution to establish standards for the acceptability of, and limits on, the use of interest reserves.

- The FDIC, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), and the Federal Reserve Board (FRB) address the use of interest reserves as part of existing examiner guidance. Overall, this guidance reinforces the importance of providing clear standards on the use of interest reserves as part of a bank’s loan policy, monitoring the adequacy of the remaining interest reserve as part of an ADC lending project, and assessing the appropriateness of the use of interest reserves during the entire term of the loan.7

Although the Financial Accounting Standards Board has not issued any standards focused specifically on the use of interest reserves from the lender’s standpoint, longstanding accounting concepts that govern the recognition of income are applicable to interest reserves. Thus, in general, interest that has been added to the balance of a loan through the use of an interest reserve should not be recognized as income if its collectibility is not reasonably assured.8 This accounting concept has been incorporated into the criteria for placing an asset in nonaccrual status for purposes of the Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Report). The Call Report instructions present these criteria in the general rule in the Glossary entry for “Nonaccrual Status,” which provides in part that banks should not accrue interest on any asset for which payment in full of principal or interest is not expected.9

Overall, this accounting and reporting guidance represents a framework that ensures that regulatory reports accurately reflect the economic substance of a transaction, taking into consideration a key factor that bears on whether interest income is both realized (or realizable) and earned. For example, the accrual of uncollected interest and its capitalization into the loan balance (e.g., through the use of interest reserves) will not be appropriate when an ADC loan becomes troubled and the full collection of contractual principal and interest payments is no longer expected.

Managing Potential Risks

In addition to existing regulatory and accounting guidance, a number of risk management practices are being recommended during examinations of FDIC-insured institutions with ADC portfolios. Recommended risk management practices include the following:

- Establish loan policies and procedures that detail the circumstances and types of loans where interest reserves may be used, with limits on time and amount of such reserves, including situations involving renewals, extensions, and refinancing;

- Maintain effective and ongoing controls for monitoring compliance with loan covenants for the advancement of funds and determination of default conditions, such as receipt of zoning variances and entitlements, limits on construction starts, and delivery of qualified pre-sales;

- Periodically evaluate and monitor real estate market conditions by independently analyzing demand, supply, and price fluctuations for properties being developed;

- Periodically reexamine property appraisals and establish steps to ensure proper evaluation of collateral when material changes occur in the real estate market;

- Regularly obtain sufficient current financial statements on the borrowing entity and guarantors to perform a global cash-flow analysis and examine the potential pressures of other projects and financial commitments; and

- Maintain effective procedures for monitoring ADC projects to ensure that loan underwriting and oversight are appropriate in light of the project’s status, the borrower’s financial condition, and the collateral protection based on present market conditions.

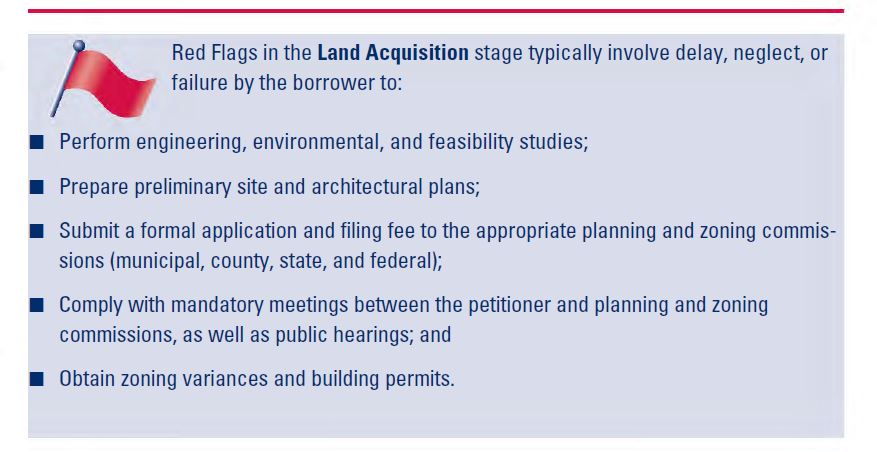

In addition, banks should implement monitoring procedures to ensure that appropriate action is taken if and when “red flags” emerge. Each phase of an ADC loan carries with it particular vulnerabilities (as discussed below). The timely recognition of potential problems will help lenders ensure that the loan is appropriately administered and reported on its financial statements. Of particular importance is the lender’s assessment of whether the use of an interest reserve remains appropriate given emerging risks or weaknesses in the ADC credit.

Acquisition

When acquiring land, the borrower generally does not yet have approval to develop the property. During this period, a number of rezoning and permitting obstacles may arise that could significantly delay or never allow the proposed project to develop as intended.

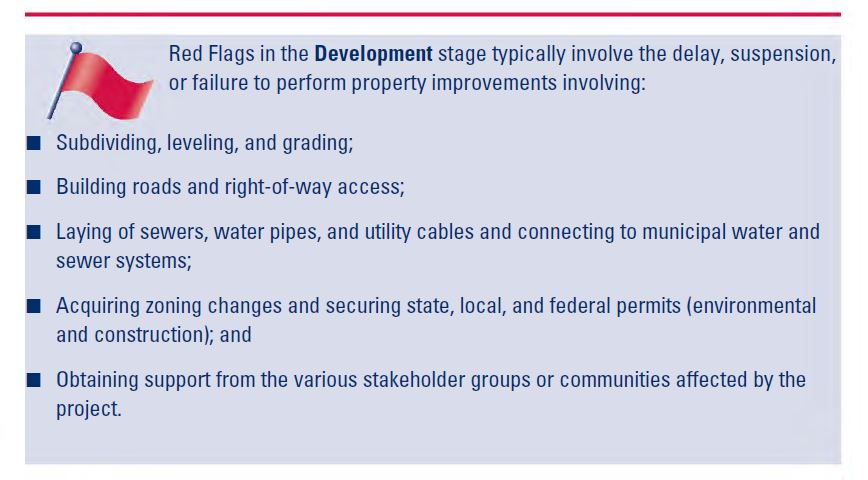

Development

After the property is acquired and necessary approvals are obtained, the land is developed for future construction of homes, commercial space, or other planned structures. During development, the lender must ensure that the borrower is using loan proceeds to convert the property into construction-ready building sites. Many factors can delay the scheduled start and completion of a real estate development project that could cause significant cost overruns and prevent the borrower’s ability to procure permanent financing or inhibit ADC project sales or lease-up.

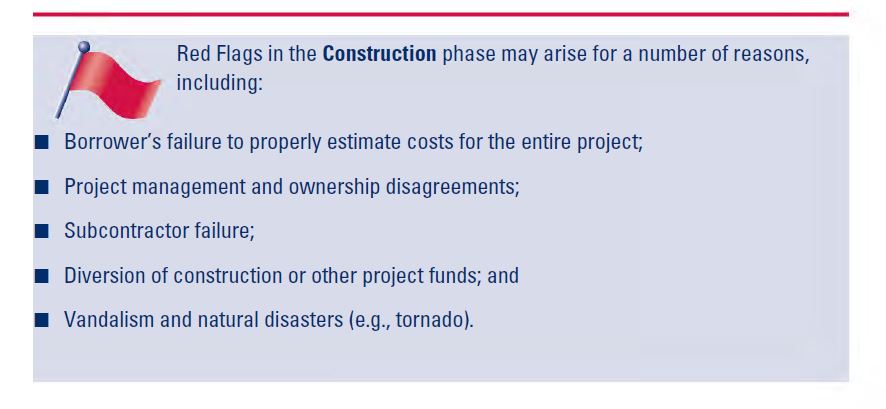

Construction

Once the property is developed, the proposed structure(s) are built. Potential risks that emerge during the construction period could determine whether the project will be completed on schedule and at the projected cost.

Another critical red flag that can occur during any phase of an ADC loan is a change in economic or real estate market conditions. Adverse changes in the economy or real estate markets can lower the purchase price and alter the timing of sales or leases (i.e., absorption rate) of the land or properties under development. In extreme cases, a serious downturn in market conditions can halt an ADC project whose cost to develop significantly exceeds the realizable value. These changes can materially affect the value of collateral, the borrower’s cash flow, and his or her overall ability to repay the loan. As a result, lenders should diligently monitor economic and real estate market conditions and carefully assess the effect on an ADC loan to ensure that it is properly administered and reported on financial statements.

Conclusion

In instances where lenders see red flags or an ADC project actually becomes troubled, the lender should carefully evaluate the factors underlying the borrowing relationship—including the status of the project, the financial condition of the borrower and any guarantors, and the collateral protection in light of present market conditions. Lenders should then take the necessary steps to manage the emerging risks, as well as properly report the distressed ADC loan on their regulatory reports, including for purposes of interest income recognition and the determination of an appropriate level for the allowance for loan and lease losses.

As part of an ongoing review of the ADC project, the lender should evaluate the appropriateness of the overall administration and regulatory reporting of the loan, including the accrual of uncollected interest through an interest reserve. The ongoing accrual of uncollected interest should be pursued only when the facts and circumstances underlying the ADC loan continue to reasonably support the contractual payment of principal and interest.

Santiago L. Granja

Bank Examiner

South Florida Field Territory

SGranja@fdic.gov

James W. Kroemer

Bank Examiner

Atlanta Field Office

JaKroemer@fdic.gov

John P. Henrie

Field Supervisor

Atlanta Field Office

JoHenrie@fdic.gov

1 Loan data obtained from Call Reports and Thrift Financial Reports submitted by FDIC-insured financial institutions.

2 Noncurrent level for nonfarm, nonresidential loans was 0.81 percent, and the noncurrent level for multifamily residential real estate loans was 0.76 percent. Third Quarter 2007 Quarterly Banking Profile, Chart 7, “The Noncurrent Rate of Construction Loans Has Been Rising From Historic Lows,” and Fourth Quarter 2007 Quarterly Banking Profile, Table V-A, “Loan Performance, All FDIC Insured Institutions,”https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/fdic-quarterly/index.html.

3 FIL 22-2008, http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2008/fil08022.html.

4 Neil B. Wedewer, Best Practices in Lending to Homebuilders, RMA Journal 89 (November 2006): 38–45.

5 Comptroller of the Currency, Guidelines for Capitalization of Interest on Loans, Examining Circular (EC) 229, May 1, 1985, https://www.occ.gov/static/news-issuances/bulletins/pre-1994/examining-circulars/ec-1985-229.pdf.

6 See Interagency Guidelines for Real Estate Lending Policies: 12 CFR 365 and appendix A (FDIC), http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/2000-8700.html#2000appendixatopart365; 12 CFR 34, subpart D and appendix A (OCC); 12 CFR 208, subpart E and appendix C (FRB); and 12 CFR 545 and 563 (OTS).

7 FDIC Examination Modules, Construction, and Land Development Core Analysis Procedures, November 1997. Office of Thrift Supervision’s Examination Handbook, Section 213, Asset Quality—Real Estate Lending Standards Rule, pp. 213.1–2, January 1994, https://www.occ.gov/static/ots/exam-handbook/ots-exam-handbook-213.pdf. Federal Reserve Bank’s Commercial Bank Examination Manual, Section 2100.1, Real Estate Construction Loans—Interest Reserves, November 1995.

8 See Accounting Research Bulletin No. 43, Chapter 1A, paragraph 1; Accounting Principles Board Opinion No. 10, paragraph 12; and Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 5, paragraph 84(g).

9 Instructions—Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income, Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Glossary, page A-59.