The banking industry has long relied on real estate as collateral for various types of loans. Hazard insurance has played a big role in mitigating the risk of loss of collateral value from catastrophic damage. Traditionally, examiners have cited inadequacies in collateral insurance coverage as technical exceptions when reviewing loan files. But in today’s environment, issues regarding insurance availability and affordability may soon reach beyond anything considered technical.

In this article, we present an overview of the impact of the rising cost, and in some cases the lack of availability, of wind hazard insurance, with a focus on Florida. Although the issue is not new to Florida, it has intensified to the point that it is often labeled a crisis.

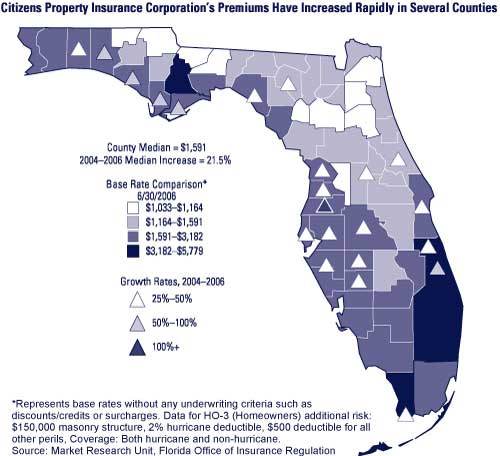

Virtually no part of the eastern and southern U.S. coastline is immune from the threat of severe storm systems. However, because of the growth in Florida’s population and infrastructure, national storm modeling firms consider Florida to have the highest level of risk in the nation for catastrophic storm damage.1 Insurers that continue to offer coverage in high-risk areas are rapidly and significantly increasing rates charged to policyholders to replenish reserves, account for the updated modeling forecasts, and pay the higher cost of reinsurance from the anticipated increased risk. Map 1 illustrates how rising rates have already squeezed many Florida homeowners in terms of their budgets and spending habits. According to the Insurance Information Institute, rates are likely to rise between 20 and 100 percent over the next year for the 43 percent of the U.S. population living in coastal areas stretching from southern Texas to the northern tip of Maine.2 Given Florida’s higher risk exposure, even higher increases in Florida would not be unlikely.

Wind insurance premium increases are having a direct negative effect on commercial and residential borrowers’ overall budgets, including their ability to service debt. It has also been widely reported that borrowers and investors are becoming hesitant to buy properties affected by significantly increasing insurance premiums. The reported slowing in real estate sales activity in Florida may be exacerbated by insurance issues.

Map 1

The considerable concern to the banking industry lies in the fact that the risk in much of its lending activity—loans secured by real estate—has historically been mitigated with property insurance, including coverage for wind damage. Prudent bankers will monitor the effect of this issue on real estate markets in their geographic areas of lending, as well as the effect on the overall economy. Concerned lenders will also consider the potential effects of changes in wind hazard insurance coverage and premiums in underwriting loans and in monitoring their overall real estate loan portfolios.

Historical and Insurance Industry Perspective

After a series of hurricanes hit Florida in the 1940s and 1950s, the state began pursuing a more consistent statewide building code. In 1974, the state implemented a uniform building code system that seemed reliable until 1992,3 when Hurricane Andrew caused $15.5 billion in damage ($21.5 billion in 2006 dollars). As a result of this damage, there were 12 insurer insolvencies and the insurance market began to collapse. The Florida legislature passed a moratorium to prevent insurers from dropping coverage to reduce their own hurricane exposure risk.4 In 2000, the legislature authorized a new uniform Florida Building Code, which became effective on March 1, 2002, making Florida the only state in the nation with a statewide building code.5

Also in 2002, the Florida legislature passed Senate Bill 1418, known as the Windstorm Bill.6 The bill created Citizens Property Insurance Corporation (Citizens), a federally tax-exempt corporation, to provide full wind, hurricane, and hail policies for residential and commercial properties that are unable to obtain insurance in the voluntary market, i.e., an insurer of last resort. Citizens receives no direct state government funding; its claims and operational costs are paid from premiums collected. If Citizens runs a deficit within a fiscal year, it has the authority to assess all property insurance companies to cover the amount of the deficit. These assessments are passed on directly to the policyholders.7

Nevertheless, a total of eight hurricanes in 2004 and 2005, including Katrina, caused nearly $36 billion in losses within Florida. As if that was not enough, hurricane forecasting models are predicting more frequent and severe storm systems in the region, which are expected to only heighten the pattern of losses.8

While residents and business owners are frustrated over increasingly expensive insurance rates, insurers must raise rates to replenish reserves in preparation for future claims. In his testimony to one of Florida’s state legislative committees, Dr. Robert P. Hartwig, senior vice president and chief economist of the Insurance Information Institute of New York, stated, “After brief periods of profitability, the market is periodically jarred by catastrophic losses that wipe out all or most of the profits since the last major event.”9

With billions of dollars in exposure being added to Florida each year from the infrastructure needed to support continuing population and economic growth, the insurance industry in general seems to be reaching the maximum level of risk it is willing to accept. Many insurance companies are no longer writing new wind hazard policies and are canceling existing policies to reduce their exposure in the state. Some insurers have completely stopped writing property insurance policies in Florida.

Between 1998 and the second quarter of 2006, the number of insurance companies writing residential policies in Florida dropped from 225 to 167. In that same time period, the number of insurance companies writing commercial policies declined from 120 to 80.10 With the burden of insuring residential and commercial properties getting pushed more and more onto the state, Citizens—whose policies number nearly 1.3 million—is writing more than 70,000 new policies per month. As the second largest homeowner insurer in Florida, next to State Farm, Citizens was exposed to $434.3 billion in insured risks as of April 6, 2007.11

The difficulties in obtaining insurance coverage are not limited to Florida. Insurance companies are either not renewing homeowner policies or are significantly raising premiums to compensate for the risk in states all along the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean coasts. For example, last year, Allstate did not renew any of its homeowner policies in New York City and three counties in the area, which Allstate considers the “catastrophe-prone areas” of New York. According to Howard Mills, New York state’s insurance superintendent, “We need to dramatically increase awareness that we are in an area not only susceptible to a hurricane, but long overdue for a hurricane. . . . There’s a reason why companies like Allstate are trying to reduce their exposure. It’s an inevitability.”12

Allstate cancelled 95,000 homeowner policies in Florida in 2005. As of November 2006, Allstate had dropped an additional 120,000 policies that had come up for renewal and is no longer writing new policies in Florida. According to Edward Liddy, Allstate’s chief executive officer, “We [Allstate] do not get adequate rates in that regulated system.”13

Rising Reinsurance Costs and Availability Issues

In 2006, then-Governor Bush appointed a special Property and Casualty Insurance Committee14 (Committee), and the Florida state legislature convened special sessions to discuss the insurance issue and reinvigorate the state-run insurance provider of last resort. According to the Committee, which was charged with researching the problems plaguing the insurance industry and offering recommendations to stabilize insurance rates for homeowners and commercial property owners, “Reinsurance capacity for Florida property risk is nearly tapped out.”15 (See text box “Florida Addresses the Insurance Crisis” for more discussion of actions being taken within the state.) With the insurance industry’s exposure rising so significantly, rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch have begun requesting that reinsurance companies infuse or retain more capital or curtail their exposure—or risk being rated less favorably.

Potential Economic Impact

The economic impact of rising insurance costs on Florida and in other parts of the nation is difficult to quantify. According to the Florida Demographic Estimating Conference data as of February 19, 2007, over the next ten years, Florida’s population will grow by 3.8 million, or 21 percent, compared to a growth of 3.7 million, or 25 percent, over the previous ten-year period. There is concern, however, that the wind-hazard insurance crisis, particularly in and around the coastal areas of the state, could adversely affect the normally robust in-migration and investment in Florida real estate of all types. If in-migration were to slow significantly, economic growth in Florida would also be expected to slow.

Jack McCabe, a real estate consultant in Deerfield Beach, Florida, reported, “We are seeing insurance rates 200 to 300 percent more than a year ago,” and higher insurance costs have contributed to the sluggish real estate market. Mr. McCabe added that “it makes Florida look not as affordable for vacation home buyers.”16

In July 2006, The New York Times featured an article in its National Perspectives section on so-called “halfbacks,” natives of northern states who retire to Florida but later change their minds and move “half way” back north. They are leaving Florida to live in states to the north, such as Tennessee, to take advantage of cheaper real estate prices and to escape rising insurance costs and other hurricane-related expenses. Bob Gilley, principal owner of Tellico Lake Realty in Tennessee, recently reported that 40 percent of the people coming to Tellico are from Florida.17

Data provided by the Florida Association of Realtors show that Florida’s existing-home sales declined each month in 2006 as compared with a year earlier; the number of existing-home sales in December 2006 was 29 percent below the sales of existing homes in December 2005. While there are certainly a number of factors tied to the declining sales, the cost of wind hazard insurance may be a contributing factor.

Florida Addresses the Insurance Crisis |

||

|---|---|---|

| Florida legislators and business interests have established committees, task forces, and programs to begin to sort through possible solutions to the problem. Recent actions include the following: | ||

|

|

|

| a House Bill 1A, January 25, 2007. See www.myfloridahouse.gov. b Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee, Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, November 15, 2006, pp. 47–48. c Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, pp. 28–29. d See www.mysafefloridahome.com. e “FBA Announces Insurance Agenda,” September 28, 2006. |

||

Impact on Insured Financial Institutions

Commercial real estate (CRE) lending is a key component of lending programs for many Florida financial institutions. Acquisition, construction, and development loans are a significant portion of CRE lending in Florida community banks. This lending is a niche for many community banks that feel they can compete with larger institutions based on local decision making and personal service. A slowdown in real estate development and investment caused by the rising cost of wind insurance could affect the ability of some smaller banks to thrive. Moreover, underinsured or uninsured collateral, declining collateral values, and declining debt-service coverage expose lenders to more risk of default and loss.

Banks are facing a number of situations brought on by the insurance crisis. Since summer 2006, the FDIC’s Atlanta Region has been tracking Florida bank examination findings as they relate to the cost and availability of wind hazard insurance. Examiners are also closely monitoring issues related to wind insurance and have discussed the actual and potential effects with the industry and other regulators in various forums. The examples below are indicative of what examiners have encountered:

- Investors are declining to purchase Florida real estate because of the prohibitive cost or lack of available wind hazard insurance.

- Borrowers are reporting policy nonrenewals and cancellations. Some banks report a slight increase in the use of forced-placed insurance as some borrowers are unable to find insurance.18 So far, these banks have been able to find policies, although at a higher cost.

- Insurance premiums are increasing—in excess of 500 percent for some borrowers.

- Some banks are considering approving loans without insurance where the land-only value is twice the loan balance.

- Some banks are requiring more collateral in consideration for waiving full insurance coverage; others are refusing to waive insurance at all.

- Borrowers are increasing deductibles to help curb the increases in premiums for wind hazard insurance on collateral.

- Some borrowers have considered self-insuring collateral.

Other federal banking agencies and the state of Florida’s Office of Financial Regulation report similar findings.

While troubling, these situations have not yet risen to a level that has substantially elevated the risk profile of a particular bank. However, Florida bankers are generally concerned and are closely monitoring the effects of the wind insurance crisis on their banks.

Prudent Risk Management Practices

No federal banking statute or regulation requires full hazard insurance coverage on all real estate collateral improvements or bank premises, although some of the federally sponsored lending organizations (Federal Housing Administration, Federal National Mortgage Association, Federal Home Loan and Mortgage Corporation, Small Business Administration, etc.) may require full insurance coverage prior to committing to purchase or guarantee all or part of commercial or residential real estate loans. States vary as to insurance requirements, and Florida has no statutes or regulations requiring full wind insurance protection of loan collateral or bank premises. FDIC Rules and Regulations (see 12 CFR 365) require prudent real estate lending policies, which would include the general requirement of insurance to enhance loan quality. However, this requirement is applied on a macro lending basis. Individual loan exceptions are normally listed as technical exceptions in the Report of Examination and not criticized unless excessive.

Examiners in the FDIC’s Atlanta Region were recently reminded that insurance coverage should be reviewed as part of the normal loan review and examination function. As is normal for any emerging risk, examiners are expected to ensure that banks monitor the insurance situation as it affects loan collateral and make reasonable documented efforts to maintain sufficient insurance. Examiners are not expected to criticize banks when uninsured or underinsured collateral results from circumstances beyond management’s control.

The FDIC is monitoring significant insurance issues closely and is communicating with the other regulatory agencies and the industry to keep to the forefront emerging risk management, asset quality, and consumer affordability issues. The wind insurance crisis poses potentially difficult decisions for bankers regarding the acquisition of insurance for existing loan collateral or whether certain loans can be originated without the benefit of wind insurance. As with any emerging risk, prudent considerations and practices of bankers may include

- Ensuring that lending policies and procedures address insurance requirements and the reporting of exceptions to the board of directors of the financial institution;

- Ensuring that mortgage loan agreements and other pertinent documentation address insurance requirements;

- Making reasonable, documented efforts to obtain and maintain sufficient insurance coverage on collateral;

- Including potential hazard insurance effects in the underwriting and ongoing analysis of debt service; and

- Considering significant insurance issues when analyzing the allowance for loan and lease losses.

Bank Premises Insurance Coverage

Banks’ lending activities are not the only area affected by the rising cost of insurance. Banks generally insure their own premises against the possibilities of fire or storm damage using extended insurance packages that indemnify against losses from windstorms, cyclones, tornados, hail, and other natural disasters. In evaluating the effectiveness of a bank’s risk management program, examiners look to see that management determines if, and how much, extended coverage is warranted.19 Variables for both examiners and bankers to consider include the locations of the bank premises, the probability of storm occurrence, the number and locations of bank branches, the adequacy of disaster recovery plans, the bank’s capital level, and the amount of risk the board of directors is ultimately willing to take.

Most banks have prudently acquired property insurance as a cost-effective means of hedging against a catastrophic event. However, some Florida banks have not been able to secure the continuation of full windstorm coverage for some or all of their buildings. When such insurance is unavailable or otherwise cost-prohibitive, banks are expected to continue working to obtain adequate coverage and to provide capital at sufficient levels to absorb potential wind damage expenses not covered by insurance, while also following accounting rules regarding the establishment of contingency reserves if necessary. As with insurance for collateral, examiners are expected to ensure that banks monitor their insurance situation with respect to bank premises and make reasonable, documented efforts to maintain sufficient coverage.

Looking Ahead

While the Florida legislature, community groups, and industry associations have worked diligently to provide relief to home and business owners, the 2007 hurricane season is fast approaching. Forecasters predict the 2007 Atlantic hurricane season will be more active than the average for the 1950–2000 seasons. They further predict a 40 percent probability for at least one major (category 3, 4, or 5) hurricane landfall for the U.S. coast, including the Florida peninsula. (This compares with an average probability of 31 percent for the last century.)20 With each new hurricane season comes the potential for damage and losses that could put further pressures on the insurance industry. However, effective risk management practices may help to lessen the impact on financial institutions.

Insurance is a highly valued tool for mitigating credit risk, but problems with maintaining affordable insurance are forcing lenders and borrowers alike to rethink what makes a sound loan and investment. Regulators, bankers, and developers all understand just how sensitive the value and debt-service capability can be for an income-producing property when insurance costs materially change. Increasing insurance costs have cut into profits and reduced disposable cash, and they have the potential to negatively affect collateral values. While the FDIC has not seen significant deterioration in individual banks, examiners will be looking for prudent bank practices, such as monitoring real estate collateral, taking reasonable precautions in keeping collateral insured, stress testing loan-to-values and debt-service abilities, and documenting banks’ efforts. Although no one knows when another catastrophe might occur, it is critical for institutions to continue to employ proper risk mitigation efforts to protect against possible losses.

Michael T. Register

Examiner,

Tampa, FL

Christopher T. Hall

Examiner,

Tampa, FL

Devin A. Baillairgé

Examiner,

Tampa, FL

David Crumby

Assistant Regional Director,

Atlanta, GA

1 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee, Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, November 15, 2006, p. 2.

2 John Simmons, “Risky Business: With $58 Billion in Claims to Pay for Last Year Alone, U.S. Insurers Are Jacking Rates, Canceling Policies and Learning to Cope with Climate Change,” Fortune Magazine (November 2, 2006), retrieved March 26, 2007, from http://money.cnn.com/ magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/09/04/8384736/index.htm.

3 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, p. 33.

4 Office of Insurance Regulation, Doing Business in Florida’s Property Insurance Marketplace, August 12, 2006, p. 7.

5 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, pp. 33–34.

6 Senate Bill 1418 can be retrieved from the Florida legislature’s website at www.leg.state.fl.us/session/index.cfm?mode=Bills&Submenu=1&BI_Mode=ViewBillInfo&Billnum=1418&Year=2002.

7 My Florida Insurance Reform, “Why am I being assessed for Citizens Insurance if they are not my insurer?”.

8 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, p. 25.

9 “Overview of Florida Hurricane Insurance Market Economics,” testimony delivered on January 19, 2005, by Robert P. Hartwig, Ph.D., CPCU, to the Florida Joint Select Committee on Hurricane Insurance.

10 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, p. 15.

11 “Policies in Force and Exposure,” retrieved April 23, 2007, from www.citizensfla.com.

12 Jeff Vandam, “Storm Fears Touch Off a Scramble for Insurance,” New York Times (August 27, 2006), retrieved March 10, 2007, from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B04E5D8133EF934A1575BC0A9609C8B63.

13 Simmons, “Risky Business.”

14 The Committee was formed on June 27, 2006, through Executive Order Number 06-150. See www.myfloridainsurancereform.com.

15 Property and Casualty Insurance Reform Committee Final Report and Recommendations, p. 51.

16 Amy Gunderson, “Home Away; Bracing for Higher Premiums,” New York Times (January 3, 2007), retrieved February 12, 2007, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9805E4DD1130F930A35752C0A9619C8B63.

17 Lisa Chamberlain, “Drawn to Eastern Tennessee’s Natural Beauty,” New York Times (July 9, 2006), retrieved January 14, 2007, from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B03E5D81330F93AA35754C0A9609C8B63&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss.

18 Force placing is a normal part of a loan agreement where the bank obtains and directly pays for an insurance policy and passes the cost on to the borrower.

19 FDIC, Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies, Section 3.5, “Premises and Equipment,” https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/safety/manual/.

20 Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray, “Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007,” Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University, December 8, 2006.