During the year 2010, legislators and regulators undertook a number of significant regulatory reforms in response to the financial crisis. One important theme of these reforms is the need for banking organizations to have stronger capital positions to weather periods of economic stress. This paper discusses one component of regulatory capital that was the subject of significant discussion, debate, and ultimately, reform during 2010: trust preferred securities (TruPS) issued by Bank Holding Companies (BHCs).

TruPS are hybrid securities that are included in regulatory tier 1 capital for BHCs and whose dividend payments are tax deductible for the issuer. Since the Federal Reserve Board's (Federal Reserve) 1996 decision to allow TruPS to meet a portion of BHCs' tier 1 capital requirements, many banking organizations have found these instruments attractive because of their tax-deductible status and because the increased leverage provided from their issuance can boost return on equity (ROE).

The increased leverage implied by the use of TruPS is a two-edged sword. Evidence suggests that banking organizations that issued these instruments were weaker as a result, took more risks, and failed more often than those that did not. The unsatisfactory experience with these instruments was one factor that set the stage for reforms that will require banking organizations to hold higher quality capital in the future.

An Introduction to TruPS

The significant use of TruPS on BHC balance sheets dates to an October 21, 1996 press release issued by the Federal Reserve. The press release described a financing structure in which a BHC creates a wholly owned special purpose entity (SPE). The SPE issues cumulative preferred stock to investors. The BHC then borrows the proceeds from the SPE using a long-term subordinated note. Under then current accounting rules, the BHC consolidated the SPE, and the financing transaction gave rise to a minority interest in the consolidated subsidiary. The press release announced that under certain conditions, this minority interest in the SPE would meet a portion of the tier 1 capital requirements for BHCs.

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in use at the time of the 1996 announcement masked the underlying economics of the transaction: the BHC was in effect issuing term subordinated debt into the marketplace and it was this subordinated debt that really was being permitted in tier 1 capital. Since the SPE's sole asset is the subordinated note from its parent BHC, any dividend payments the SPE pays to the trust preferred investors are, in substance, simply the BHC's interest payments on the subordinated debt. Moreover, while the TruPS themselves have no maturity date, their effective life is limited as the trust typically terminates at the maturity date of the subordinated debt, by which time the BHC bears a legal obligation to repay this debt in accordance with its contractual terms.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recognized the economic substance of the trust preferred structure as a debt issuance of the BHC. As described by the Federal Reserve in a 2005 rulemaking, "A key advantage of TruPS to BHCs is that for tax purposes the dividends paid on TruPS, unlike those paid on directly issued preferred stock, are a tax-deductible interest expense. The Internal Revenue Service ignores the trust and focuses on the interest payments on the underlying subordinated note."1

TruPS became extremely popular among banking organizations because their dividends are tax deductible and their issuance does not dilute equity of the BHC. Of the roughly 1,025 BHCs reporting on form Y-9C as of June 30, 2010, nearly two-thirds (664) reported some amount of TruPS in their tier 1 capital during the past five years, with close to half of those (308) reporting TruPS exceeding 25 percent of tier 1 capital at one point during that time. Roughly half the 308 banking companies with higher dependence on TruPS were smaller banking companies with total assets of $1 billion or less.

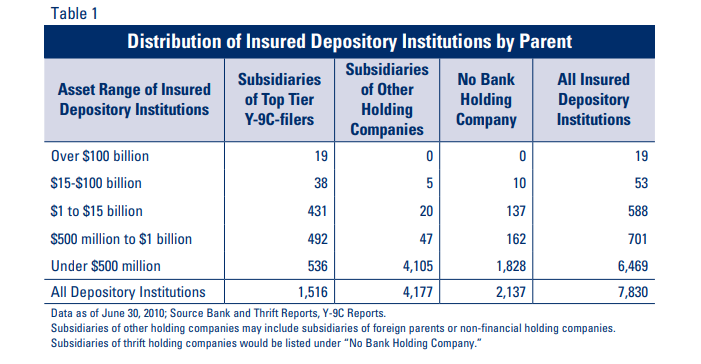

The Federal Reserve's decision to allow TruPS to satisfy part of BHCs' tier 1 capital requirement was important to insured banks as well. As indicated in Table 1, more than 70 percent of insured banks are subsidiaries of a bank holding company. Although banks are separately regulated from their parent holding companies, many are linked to their parent through capital transfers, including dividends from the bank to the holding company and capital infusions from the parent company down-streamed to the bank.

Smaller bank holding companies typically did not bring TruPS directly to market. Instead, these organizations often would sell their TruPS into a collateralized debt obligation (CDO). These CDOs, which commingled TruPS issued by smaller banking organizations and other entities, were tranched and sold to investors. Fitch reported that since the year 2000, 1,813 banking entities issued TruPS that were purchased by TruPS CDOs, in an aggregate amount of roughly $38 billion.2 The federal banking agencies deemed these CDOs permissible investments for insured institutions,3 meaning that banking organizations could both issue these securities as capital and purchase them as debt.

TruPS are rated as debt instruments by the rating agencies. Correspondingly, for issuers, the rating agencies substantially discounted the contribution of TruPS to the capital strength of banking organizations. For example, according to Moody's, "[w]e have always considered TruPS to be far more debt-like in nature, and have generally not assigned them any 'equity credit' in evaluating the capital structure of highly rated issuers."4

The Federal Reserve imposed a number of conditions that, in its view, warranted allowing TruPS to meet a portion of BHCs' tier 1 capital requirements despite their economic substance as debt. Conditions for tier 1 status included the ability to defer dividends for at least five years; subordination of the BHC's long-term subordinated note to the SPE to other BHC debt including all other subordinated debt; maturity of this intercompany subordinated note at the longest feasible maturity; a prohibition on redemption without prior approval of the Federal Reserve; and a requirement for the TruPS along with other cumulative preferred stock to comprise no more than 25 percent of the BHC's core capital elements.

One of the most important features of TruPS the Federal Reserve relied upon in granting tier 1 capital status was the ability to defer dividends. This feature allows the BHC some flexibility to stop the interest payments on the subordinated debt and redirect cash flows within the company during a period of adversity. Because of the cumulative dividend obligation, however, the deferral of dividends does not protect the accounting solvency of the organization. Specifically, during the deferral period, the BHC must record a liability and interest expense for the amount of the accrued but deferred interest payable on the subordinated debt at the end of each period in which dividends are deferred, and this liability and the related interest expense continue to accrue at the interest rate on the subordinated debt until all deferred interest and the corresponding amount of deferred dividends are paid.

The events that transpire in the event of deferral and ultimate non-payment of dividends are important to understanding the limits to the loss absorption capacity of TruPS. As described by the Federal Reserve, "The terms of the TruPS allow dividends to be deferred for at least a twenty-consecutive quarter period without creating an event of default or acceleration. After the deferral of dividends for this twenty quarter period, if the BHC fails to pay the cumulative dividend amount owed to investors, an event of default and acceleration occurs, giving [trust preferred] investors the right to take hold of the subordinated note issued by the BHC [to the SPE]. At the same time, the BHC's obligation to pay principal and interest on the underlying junior subordinated note accelerates and the note becomes immediately due and payable."5

At the end of the deferral period, then, the TruPS investors would be left holding a deeply subordinated note of the BHC, which would be likely to absorb substantial loss in the event of the BHC's failure. As noted, however, all cumulative dividend arrearages must be paid in full if the BHC is to continue to operate as a going concern.

TruPS and Regulatory Capital for Insured Banks

The most important function of bank capital is to absorb unexpected losses while the bank continues to operate as a going concern. This shock-absorber function increases the likelihood that a bank can withstand a period of economic adversity, while system-wide, adequate capital ensures the banking industry as a whole can continue to lend during a downturn. A secondary function of bank capital is to absorb losses after the bank has failed, thereby reducing the cost of the failure to the deposit insurance fund. Capital also plays an important role in mitigating moral hazard by ensuring that the owners, who reap the rewards when a bank's risk-taking is successful, have a meaningful stake at risk.

Bank regulators distinguish between "core capital elements" (tier 1) and "supplementary capital elements" (tier 2). Generally speaking, core capital elements are those that are fully available to absorb losses while the banking organization operates as a going concern. Regulators expect core or tier 1 capital to consist predominantly of voting common equity. Other permissible tier 1 capital elements for insured banks are noncumulative perpetual preferred stock and, in certain circumstances, minority interest in consolidated subsidiaries. In addition, certain assets deemed to be insufficiently reliable or permanent are deducted for purposes of calculating a bank's tier 1 capital.6

Voting common equity is the ownership stake of those ultimately in control of the bank's risk-taking, has no contractual interest or dividend payments or redemption rights, and therefore is fully available to absorb losses while the bank continues to operate. Regulators view voting common equity, net of deductions, as the highest form of bank capital. Recently, this view was reinforced by an agreement announced by the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision on September 12, 2010.7

The regulatory capital treatment of preferred stock issued by insured banks illustrates the conceptual view of tier 1 capital just described. Preferred stock is senior to equity in liquidation but junior to other creditors. It may carry a stated dividend and, like a bond, may be rated by the major credit ratings agencies. To receive tier 1 capital status, however, an insured bank's preferred stock must not have a maturity date or any feature that will, legally or as a practical matter, require future redemption. Moreover, to qualify for tier 1 capital status for insured banks, the preferred stock cannot have a cumulative dividend obligation. Given these restrictions, noncumulative perpetual preferred stock is viewed by the banking agencies as having sufficient ability to fully participate in losses on a going-concern basis to warrant its inclusion in insured banks' tier 1 capital.

Historically, dating back to at least 1989, the definition of tier 1 capital at BHCs has been more permissive than the corresponding definition for insured banks. For example, since 1989 the Federal Reserve has permitted qualifying cumulative perpetual preferred securities to comprise up to 25 percent of a BHC's tier 1 capital.8 In contrast, cumulative preferred stock does not qualify as tier 1 capital for insured banks. As another example of differences in tier 1 capital definitions between BHCs and insured banks, mandatory convertible securities are subordinated debt securities that convert to common stock or perpetual preferred stock at a future date. For an insured bank, these securities are considered hybrid capital instruments that, subject to certain conditions, qualify as tier 2 capital. For BHCs, however, subject to prior approval by the Federal Reserve in each instance, these securities may qualify as tier 1 capital.

The 1996 approval of TruPS as tier 1 capital for BHCs was based in part on the fact that the cumulative preferred stock issued to investors by the SPE appeared on the BHC's balance sheet as a minority interest in a consolidated subsidiary. Since the minority interest consisted of cumulative preferred stock, however, this minority interest would not have qualified for tier 1 capital status if the SPE had been a subsidiary of an insured bank.9

Financial Reporting for TruPS

As noted in the first section, the economic substance of the issuance of TruPS was that the BHC was financing itself with subordinated debt. Financial reporting requirements eventually came to recognize this reality with the issuance by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in January 2003 of FASB Interpretation No. 46, Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities (FIN 46), followed by a revision (FIN 46R) in December of that year. These changes recognized the substance of the TruPS structure by normally no longer requiring the consolidation of the SPE created to issue the TruPS. As a consequence, BHCs began to report the subordinated debt issued to the SPE as a liability instead of reporting the preferred stock as a minority interest in a consolidated subsidiary.

In its March 2005 rulemaking10 to address the effects of the accounting change, the Federal Reserve decided to retain the tier 1 capital status of TruPS for BHCs, although with a lower limit for large, internationally active organizations. The rule specified that these large banks were required to reduce their reliance on restricted core capital elements11 to 15 percent of core capital elements (including restricted core capital elements)12 net of goodwill less any associated deferred tax liability, down from 25 percent of core capital elements before the deduction of goodwill, by March 31, 2009.13

The Federal Reserve's limit for restricted core capital elements for smaller organizations remained at 25 percent of the sum of core capital elements (including restricted core capital elements), net of goodwill less any associated deferred tax liability. To put this another way, TruPS could comprise up to 25 percent of a grossed up tier 1 capital number that did not reflect deductions for disallowed intangible assets, disallowed deferred tax assets and other deductions. Thus, in effect, TruPS for smaller organizations could—and as described below, often did—comprise significantly more than 25 percent of actual tier 1 capital.

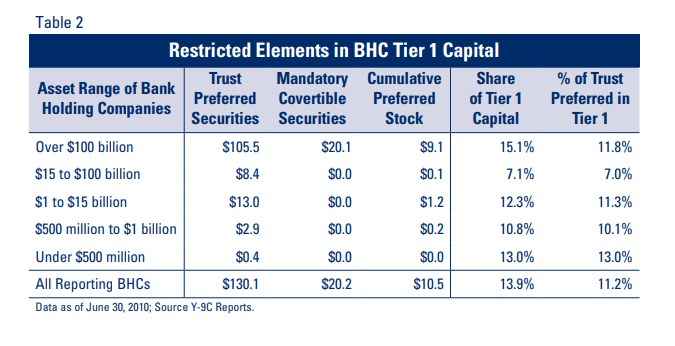

TruPS are by far the most popular of the unique tier 1 capital elements available only to BHCs. As indicated in Table 2, as of June 30, 2010, the amount of qualifying TruPS outstanding in tier 1 capital at BHCs reporting on form Y-9C was $130 billion, representing the majority of the roughly $161 billion in total restricted capital items.14 While most of the dollar volume of these items was at the largest banks, smaller bank holding companies as a group had the highest reliance on TruPS in tier 1.

TruPS in a Stressed Banking Environment

The experience of the past several years suggests that BHCs that relied on TruPS as regulatory capital were weaker because of that reliance, assumed more risk, and failed at a higher rate than other BHCs. There are four reasons for this.

- First, reliance on TruPS increased the financial leverage in banking organizations, making them less resilient in the face of adversity.

- Second, heavy users of TruPS appear to have levered the proceeds to make riskier than normal loans, perhaps in response to pressures to meet aggressive return on equity targets.

- Third, when an organization has issued TruPS, the FDIC has more difficulty attracting investors to the institution in a stressed situation while the institution remains open. This increases the likelihood of failure rather than rescue, which increases the FDIC's costs.

- Finally, when TruPS are issued by one BHC as capital and owned by another bank, the resulting double counting of capital in the banking system creates inter-linkages that magnify the effects of losses.

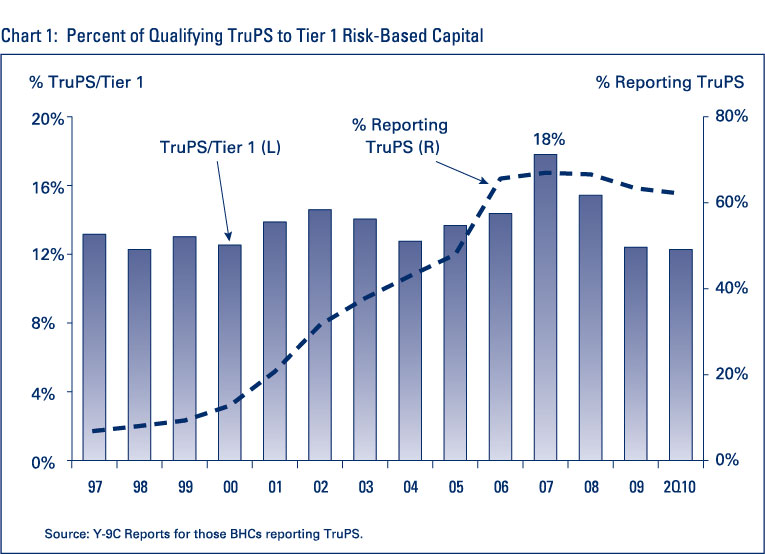

Leverage. As noted earlier in the paper, issuing TruPS became very popular among banking organizations. Chart 1 shows the percentage of BHCs (those filing a form Y-9C) that have used TruPS over time to meet part of their tier 1 capital requirements. Among those BHCs that issued TruPS, the percentage of TruPS in tier 1 capital increased steadily during the years leading up to 2007, when the average reached 18 percent.

The TruPS dependence figures reported in Chart 1 are averages. Many BHCs' TruPS comprised more than 25 percent of their tier 1 capital. For example, almost one-half of the 664 BHCs that filed a form Y-9C as of June 30, 2010 and included TruPS as regulatory capital between 2005 and 2009 reported that their TruPS represented over 25 percent of tier 1 capital at one time.

A small minority of the many smaller BHCs that did not file a form Y-9C also issued TruPS. Specifically, 685 of the 4,025 small parent BHCs reporting in June 2010 had subordinated debt outstanding to SPEs that issued TruPS. Among these 685 small BHCs, comprising 734 FDIC-insured subsidiaries, reliance on TruPS was very high. In aggregate, TruPS stood at about 35 percent of GAAP equity for these 685 organizations.

Including TruPS within tier 1 capital at these levels materially reduces a banking organization's ability to absorb losses. For example, a BHC reporting a tier 1 leverage ratio of 5 percent, of which 25 percent or 1.25 percentage points consists of TruPS, has loss absorbing capital of 3.75 percent of assets, a level of capital that would result in an undercapitalized designation for an insured bank. If losses equal to 1 percent of assets are sustained, the organization will report a tier 1 leverage ratio of 4 percent but have loss absorbing capital of 2.75 percent of assets, resulting in a significantly undercapitalized designation if the entity were an insured bank.

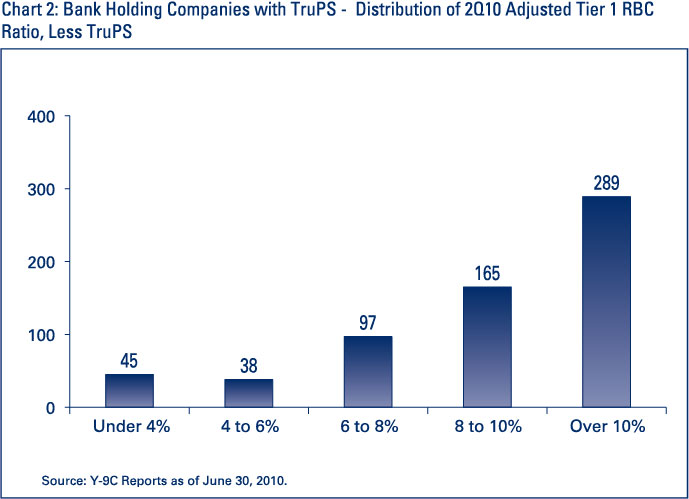

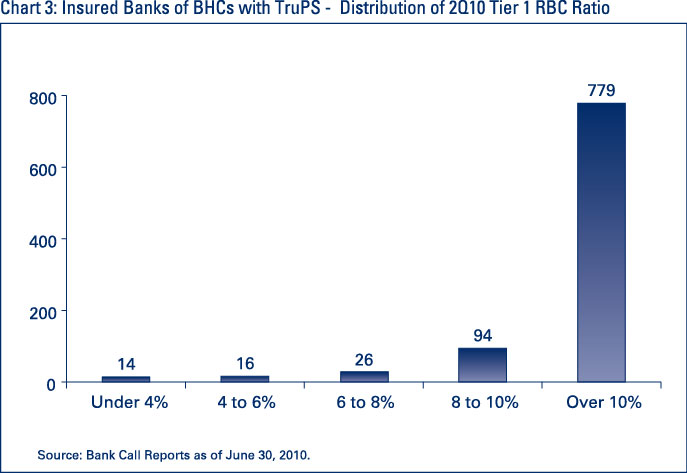

Charts 2 and 3 convey a sense of how the use of TruPS by BHCs has reduced the effective loss absorbing capital of these organizations relative to the capital strength of their insured bank subsidiaries. The 634 BHCs that reported TruPS in their tier 1 capital at June 30, 2010, had 929 insured depository institution subsidiaries. Only 6 percent of all these insured banks reported tier 1 risk-based capital ratios (not including TruPS) of less than 8 percent of risk-weighted assets. Another 10 percent of these insured banks reported tier 1 risk-based capital ratios of between 8 percent and 10 percent of risk-weighted assets.

When the same entities are viewed as consolidated BHCs, their distribution of capital ratios is markedly weaker. About 28 percent of these 634 BHCs would have tier 1 risk-based capital ratios of less than 8 percent if their TruPS were excluded from tier 1 capital as it is excluded for an insured bank. Another 26 percent of these BHCs would have reported tier 1 risk-based capital ratios of between 8 percent and 10 percent of risk-weighted assets if their TruPS were excluded from tier 1 capital.

In short, the use of TruPS in tier 1 capital enabled these banking organizations, as a group, to operate with substantially less loss absorbing capital on a consolidated basis than did their insured bank subsidiaries.

Risk profile. BHCs that relied on TruPS to meet tier 1 capital requirements exhibited a higher risk profile than other BHCs. Moreover, BHCs with the heaviest reliance on TruPS exhibited a higher risk profile than BHCs that used TruPS but had less reliance on them.

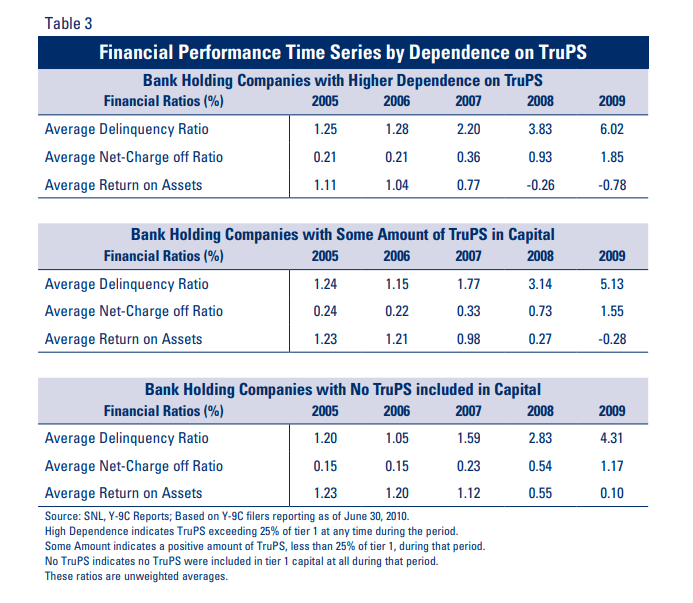

Table 3 shows selected financial ratios for the 1,025 bank holding companies filing form Y-9C as of June 30, 2010 over the five-year period 2005-2009. The 308 BHCs with a higher dependence on TruPS showed less favorable financial performance compared to those that had a smaller amount of TruPS and those that had no TruPS during that period. Delinquency ratios and net charge-offs were higher, and earnings were lower. Similar trends were noted at the insured banking subsidiaries of these holding companies, as is expected since the assets of most of these BHCs consist almost entirely of the assets of their subsidiary banks.

The BHCs that relied on TruPS were also much more likely to exhibit concentrations in construction and development (C&D) lending and to be involved in non-traditional mortgage lending. For example, roughly 70 percent of BHCs with high dependence on TruPS had C&D concentrations over 100 percent of risk-based capital at some point during the past 5 years, compared to over 50 percent of BHCs with some TruPS, and nearly 40 percent of BHCs with no TruPS. BHCs with TruPS also held 99 percent of the volume of closed-end loans with negative amortization features during that time period.

This suggests that BHCs' use of TruPS correlated to some degree with their appetite for risk. For a given level of tier 1 capital, having more TruPS and less equity acts to directly boost ROE. Institutions whose ROE focus was primarily short term, as opposed to a focus on the sustainability of earnings, may have been motivated both to accept the higher leverage implied by the use of TruPS, and to invest in riskier portfolios.

Certainly, all the indicators cited in Table 3 suggest that the portfolios of the "high TruPS" BHCs were riskier than the portfolios of other BHCs with TruPS, and riskier still than the portfolios of BHCs with no TruPS.

Obstacles to recapitalization. In the preamble to a 1991 proposed rule, the Federal Reserve wrote of the issues that could arise from reliance on cumulative preferred stock in a bank's capital. "A principal reason for the [Federal Reserve] Board's decision to limit the amount of perpetual preferred stock in bank holding [company] Tier 1 capital is the fact that cumulative preferred, the type of perpetual preferred most prevalent in U.S. financial markets, normally involves preset dividends that cannot be cancelled, but only deferred. An institution that passes dividends on cumulative preferred stock must pay off any accumulated arrearages before it can resume payment of its common stock dividends. Thus, undue reliance on cumulative perpetual preferred stock and the related possibility of large dividend arrearages could complicate an organization's ability to raise new common equity in times of financial difficulty."15

In retrospect, these words foreshadowed issues that the banking agencies would have to confront during the current crisis. As noted earlier, deferring dividends on TruPS does not protect the accounting solvency of the organization and, when the interest payments on the related subordinated debt also are deferred, results in a build-up of a dividend arrearage that accumulates at the stated dividend rate. In a situation where a capital injection into an open bank is being contemplated, the trust preferred investors may not have incentive to accept a reduction in their claims.

The FDIC's experience has been that the holders of TruPS have been an impediment to recapitalizations or sales of troubled banks. Potential investors in an open but troubled bank may need some reduction in claims from the TruPS holders to make a transaction feasible. However, there have been a number of occasions where, even when the common shareholders are poised to vote in favor of a transaction or sale (even one that results in significant dilution of equity), the trust preferred holders will not vote at all, or will not vote in favor of the transaction. One of the problems is that many trust preferred issues are in pools, which the holders say precludes voting on particular exchanges or discounts (e.g., BHC A offers to exchange its TruPS for common equity, or offers to redeem its TruPS at a specified discount). In some cases, the FDIC has found that downgraded TruPS are held by private equity investors who purchased the securities at a steep discount to par and may wish to hold out for a large "upside" in a transaction. In other cases, trustees of the TruPS will not vote for fear of litigation, or the percentage of TruPS holders needed to vote in favor may be very high.

Losses to holders of TruPS. As noted earlier, TruPS fulfilled a dual role for the banking system. Viewed as capital by the issuers, they carried tax deductible dividends and enhanced organizations' opportunities to boost ROE with leverage. Viewed as debt instruments, and often as highly rated instruments at that, TruPS were permissible investments for banks and grew to occupy an important niche in the investment portfolios of many of them.

Over 300 FDIC-insured institutions reported investment in TruP CDOs in their September 30, 2010 Call Reports. Insured institutions typically invested in the mezzanine classes. When issued, the mezzanine bonds were rated investment grade. Today, they are typically rated Caa or worse because of the dramatic deterioration in the underlying collateral. FitchRatings, which rates all the bonds in the TruP CDO universe, reported that nearly 34 percent of the dollar volume of trust preferred collateral that underlies the CDOs had either defaulted or deferred dividend payments as of October 31, 2010.16

TruP CDOs are typically structured into senior, mezzanine, and income classes. Performance triggers, including overcollateralization tests and interest coverage tests, are common features in these structures. These triggers essentially act as a credit enhancement to the senior bonds. When the overcollateralization performance test fails, cash flows are redirected from the mezzanine bonds to the most senior bond outstanding. With many of the TruP CDOs, overcollateralization tests that govern the mezzanine bonds have failed. Consequently, many mezzanine bonds are now nonearning assets.

Recovery rates on defaulted collateral have been nonexistent during the banking crisis and cure rates on deferring collateral have been minimal, with seven examples identified where dividend payments have been resumed since the banking crisis began.17 The high volume of nonperforming collateral means many mezzanine bondholders are, or could become, dependent on the securitization structure's excess spread, meaning the difference between the interest generated from the collateral and that owed on the various bond classes.

The banking industry has experienced significant write-downs of mezzanine bond holdings. Over the past two years, the failure of several federally insured depository institutions was due largely, or in part, to their investment in TruP CDOs.

The bottom line. It is difficult to disentangle the separate effects of higher imbedded financial leverage, a higher credit risk profile and increased difficulties with recapitalization that are associated with the issuance of TruPS. The experience with bank failures during the crisis, however, points to the role that relying on TruPS to meet a portion of their tier 1 capital requirements had in producing weaker banking organizations.

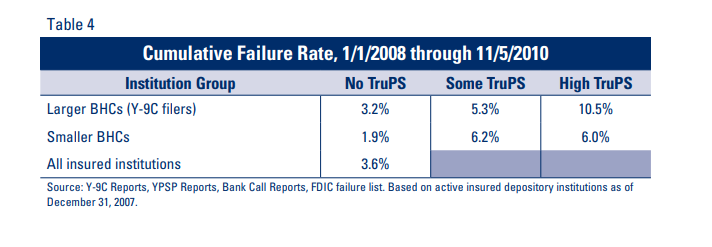

As indicated in Table 4, banking organizations issuing TruPS failed at much higher rates during the period January 1, 2008 through November 5, 2010 than did insured banks generally or insured banks in BHCs that did not issue TruPS. In the table, "No TruPS" refers to BHCs that did not report any TruPS, "some TruPS" refers to organizations with TruPS greater than zero and less than 25 percent of tier 1 capital, while "high TruPS" refers to organizations with TruPS exceeding 25 percent of tier 1 capital at the beginning of that time period (or 25 percent of equity in the case of small BHCs). More than 10 percent of the insured bank subsidiaries of the Y-9C filing BHCs with high TruPS issuance failed during this period, almost three times the failure rate of insured institutions generally.

Capital Reform

As became evident during the crisis, analysts and other market participants were ultimately looking to the tangible equity capital strength of banking organizations when assessing their capital adequacy. This is in part why U.S. bank regulators did not allow TruPS to be included in the bottom line tangible equity targets being established for the largest banks as part of the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP) conducted in the spring of 2009.

The consensus of policymaking groups reflecting on the financial crisis has been that TruPS should no longer be deemed tier 1 capital for banking organizations. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published a comprehensive capital reform paper in December 2009, "Enhancing the Resilience of the Financial System." That paper made a number of important proposals, many of which were ultimately agreed by the Committee and its parent organization, the Group of Central Bank Governors and Heads of Supervision. An important goal of these Basel 3 reforms was to strengthen the definition of regulatory capital by moving much closer to a "tangible common equity" approach. Part of this strengthening of the definition of capital included phasing out, beginning in 2013, the tier 1 capital treatment of TruPS and similar hybrid capital instruments lacking the ability to absorb losses.

In the U.S., in July 2010, Congress enacted and the President signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (the Act). The Act had a number of important purposes, one of which was to strengthen capital in the banking industry.

Section 171 of the Act (generally referred to as the Collins Amendment after Senator Susan Collins of Maine, its sponsor) contains a number of important provisions, including that the generally applicable insured bank capital requirements (and specifically including the capital elements that appear in the numerator of regulatory capital ratios) shall serve as a floor for the capital requirements applicable to depository institution holding companies.

This part of Section 171 can be viewed as affirming the concept that bank holding companies should be a source of strength for insured banks. Specifically, bank holding companies should not be a vehicle for achieving levels of financial leverage at the consolidated BHC level that are impermissible for subsidiary banks. As TruPS are impermissible as tier 1 capital elements for insured banks, under section 171 they would be (subject to specified exceptions) impermissible as tier 1 capital for BHCs.

Section 171 provides that the tier 1 capital treatment of TruPS issued before May 19, 2010, by depository institution holding companies with at least $15 billion in total consolidated assets as of year-end 2009 will be phased-out during a three-year period starting January 1, 2013. TruPS of these organizations issued on or after May 19, 2010, would not be included in tier 1 capital.

Except as described in the next paragraph, BHCs with total consolidated assets less than $15 billion as of year-end 2009, and organizations that were mutual holding companies on May 19, 2010, face the same prohibition on the inclusion of new TruPS in tier 1 capital as do the larger organizations. The key difference for these institutions is that their pre-existing TruPS (those issued before May 19, 2010) are grandfathered: that is, Section 171 does not require them to phase out these securities from their tier 1 capital.

Finally, organizations subject to the Federal Reserve's Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement (which applies to most BHCs with assets less than $500 million) are completely exempt from any requirement of Section 171.

It is anticipated that the requirements of Section 171 restricting BHCs' ability to use TruPS to satisfy tier 1 capital requirements would be implemented by Federal Reserve regulation at some future date.

Conclusion

The life of TruPS as a tier 1 capital instrument for large U.S. BHCs dates from birth in a 1996 Federal Reserve press release to a Collins Amendment-mandated sunset at year-end 2015. Their 20 year lifespan was witness to the full dynamics of both economic and regulatory cycles.

Organizations took full advantage of the opportunity to issue subordinated debt as tier 1 capital, boosting ROEs with tax deductible dividends and increased financial leverage. Institutions that relied on TruPS for regulatory capital were financially weaker for it, took more risks, and failed more frequently than those that did not. As is often the case after a crisis, reforms were put in place to correct observed problems, and the elimination of TruPS from large BHCs' tier 1 capital agreed by the Basel Committee and required by the U.S. Congress is a case in point. Moving away from reliance on TruPS and towards real loss-absorbing capital will be manageable for most institutions, will challenge some, but will in the end result in a stronger U.S. banking industry.

George E. French

Deputy Director for Policy

gfrench@fdic.gov

Andrea N. Plante

Senior Quantitative Risk Analyst

aplante@fdic.gov

Eric W. Reither

Senior Capital Markets Specialist

ereither@fdic.gov

Ryan D. Sheller

Senior Capital Markets Specialist

rsheller@fdic.gov

This article benefited from the valuable comments of Nancy W. Hunt, Associate Director; Michael Kostrna, Capital Markets Specialist; Gregory M. Quint, Capital Markets Specialist; Christopher J. Spoth, Senior Deputy Director; Paul S. Vigil, Senior Management Analyst; and James C. Watkins, Deputy Director.

1 See Risk-Based Capital Standards: Trust Preferred Securities and the Definition of Capital , 70 Fed. Reg. 11827 (March 10, 2005). http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2005/03/10/05-4690/riskbased-capital-standards-trust-preferred-securities-and-the-definition-of-capital.

2 "Fitch Bank TruPS CDO Default and Deferral Index," November 2010, Structured Credit Special Report, FitchRatings. http://www.fitchratings.com/creditdesk/reports/report_frame.cfm?rpt_id=576606.

3 See, for example, Interpretive Letter No. 777, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, April 8, 1997; and "Investments in Trust Preferred Securities," FDIC Financial Institution Letter FIL-16-99, February 19, 1999.

4 "Impact on Federal Reserve's Proposed Rule for Trust Preferred Securities on Moody's Ratings for U.S. Banks," Moody's Investors Service, May 2004. http://v3.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid=PBC_87135. (Reader must register on this site to access documents.)

5 See Risk-Based Capital Standards: Trust Preferred Securities and the Definition of Capital, 70 Fed. Reg. 11827 (March 10, 2005). http://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2005/03/10/05-4690/riskbased-capital-standards-trust-preferred-securities-and-the-definition-of-capital.

6 These deductions include goodwill and other intangible assets (except a limited amount of mortgage servicing assets, nonmortgage servicing assets, and purchased credit card relationships), certain credit-enhancing interest-only strips, certain deferred tax assets, identified losses, certain investments in financial subsidiaries and certain non-financial equity investments. These deductions, among others, are described in detail in the banking agencies' capital regulations.

7 http://www.bis.org/press/p100912.htm.

8 See 12 CFR part 225, App. A, II.A.1a(iv). http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6000-1900.html#fdic6000appendixa.

9 See Interpretive Letter No. 894, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, March 10, 2000. https://www.occ.gov/topics/charters-and-licensing/interpretations-and-actions/2000/int894.pdf.

10 See 12 CFR part 225, App.A, II.A.1.b. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6000-1900.html#fdic6000appendixa.

11 12 CFR part 225, App.A, II.A.1.a. Restricted core capital elements are defined to include qualifying cumulative perpetual preferred stock (and related surplus), minority interest related to qualifying cumulative perpetual preferred stock directly issued by a consolidated U.S. depository institution or foreign bank subsidiary (Class B minority interest), minority interest related to qualifying common or qualifying perpetual preferred stock issued by a consolidated subsidiary that is neither a U.S. depository institution nor a foreign bank (Class C minority interest) and qualifying trust preferred securities. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6000-1900.html#fdic6000appendixa.

12 12 CFR part 225, App.A, II.A.1. Core capital is defined as common stockholders' equity; qualifying noncumulative perpetual preferred stock (including related surplus); qualifying cumulative perpetual preferred stock (including related surplus); and minority interest in the equity accounts of consolidated subsidiaries. http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6000-1900.html#fdic6000appendixa.

13 12 CFR part 225, App. A, II.A.1.b. Compliance was later delayed until March 31, 2011; http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6000-1900.html#fdic6000appendixa and http://federalregister.gov/a/E9-6096.

14 "Fitch Bank TruPS CDO Default and Deferral Index," November 2010, Structured Credit Special Report, FitchRatings. http://www.fitchratings.com/creditdesk/reports/report_frame.cfm?rpt_id=576606.

15 See Notice of Proposed Revisions to Capital Adequacy Guidelines, 12 CFR parts 208 and 225, 56 Fed. Reg. 56949 (November 7, 1991).

16 "Fitch Bank TruPS CDO Default and Deferral Index," November 2010, Structured Credit Special Report, FitchRatings. http://www.fitchratings.com/creditdesk/reports/report_frame.cfm?rpt_id=576606.

17 Information based on conversation with ratings agency analyst.