The structured finance market experienced phenomenal growth and innovation during the past decade. However, recent turmoil in the credit markets has raised doubts about the future viability of some products that rely primarily on the securitization process to derive value. Significant concerns have been raised about the lack of transparency of some securitization products.

In this paper we review the availability of information about some of these complex products. Our review supports the conclusion that lack of transparency of these products is a significant problem. The paper contains a number of recommendations that we believe policymakers should consider to improve the transparency of these products. We conclude with some reminders about existing supervisory guidance that is relevant to these issues.1

Inherent Opacity in the Securitization Process

Concerns about transparency in the securitization process are not new. Transparency concerns have existed and resurfaced on occasion since the securitization business model was introduced in 1985. These concerns first centered on the lack of standardized deal terms and documentation. Over time, a measure of standardization has been introduced, especially to more “plain vanilla” securitization products, such as mortgage-backed securities.2 However, standardization and transactional transparency for more exotic forms of securitization, such as structured investment vehicles (SIVs) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), remains inadequate.3

Most structures provide general documentation about the type of underlying exposures and the credit ratings, if any, that have been assigned to the underlying exposures and the tranches of the structure itself. However, most do not provide a significant discussion concerning the specific risk drivers associated with underlying exposures, or how these risk drivers may cause the valuation of the underlying exposures and the structure itself to change in response to various economic conditions. For example, a CDO or SIV investor would generally find it difficult to determine whether an underlying exposure was subprime, or if the underlying exposure was itself exposed to subprime obligors.

The lack of transparency in complex securitization products has recently affected local government investments. News reports have stated that a number of state and municipal investment funds, such as Florida’s local government investment pool and Orange County, California, held significant investments in SIV debt, such as asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), a common short-term debt instrument issued by SIVs.4 This debt was reportedly purchased because it was AAA-rated and offered higher yields than that of other AAA-rated short-term securities. Many investors, especially government investors, operate under investment policies that limit the choice of investment instruments to only those that meet certain credit rating (for example, AAA- or AA-rated) and maturity (often short-term) criteria. As a result, these investors saw an opportunity to increase return within their investment limitations. However, few investors fully understood the risks associated with the underlying SIV structures, which have been labeled as “some of the most confusing, opaque, and illiquid debt investments ever devised.”5

During the summer of 2007, SIVs were the object of concern within the investment community when it became obvious that the opaque structure of these instruments made it virtually impossible for investors to determine the structure’s relative exposure to subprime mortgages, much less appropriately assess the risk profile of the underlying exposures. As a result, investors began to shy away from investments in SIVs, creating a liquidity crisis in the securitization market, which began in August of 2007.

Concerns also have been raised regarding the lack of transparency in securitization products that are used by corporations to achieve risk transference or as a means of off-balance sheet funding. Investors and industry watch groups have voiced concern that the accounting and disclosures for off-balance sheet transactions, as well as the complexity of many securitization structures, have left them unable to assess whether risk has been significantly transferred away from the corporate issuer.6 Although changes in accounting principles and the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 20027 have lessened concerns about financial disclosure, many investors believe that issuers continue to bear undisclosed risk. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has recently taken steps to increase transparency through the implementation of Regulation AB8 (Reg AB) which imposes initial disclosure requirements on some types of asset-backed securities.

Highlighting concerns in this respect, several large issuers of securitization products have provided considerable financial support to prevent investors in highly rated securitization tranches from recognizing losses. These issuers, while not legally compelled to provide support, did so to manage reputational risk and bolster investor confidence in subsequent securitization transactions. In addition, issuers of investment products, such as money market mutual funds, have also chosen to bear losses or provided financial support beyond their contractual requirements to protect investors from losses on commercial paper issued by CDOs and SIVs.

Another transparency concern relates to investors’ ability to properly assess the credit risk associated with the assets used to back securitization products. For instance, a residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS) can be collateralized by thousands of individual mortgages. For this reason, certain short-cuts are often used, such as accepting the reputation of various agents, for example, servicers, originators, and rating agencies, to minimize the amount of due diligence performed.

In addition to these inherent characteristics of the securitization process that promote opacity, other external issues further hinder transparency.

Roadblocks to Transparency

Lack of Secondary Market Trading Information

Little price transparency is available on most structured finance securities. Market participants attribute this to the lack of an established secondary market for these securities as most ABS and CDO investors follow a buy-and-hold strategy, with trades executed bilaterally between the investor and the dealer bank. As a result, for many product types, actual trade prices generally are not reported in organized or centralized fashion, although market participants indicate that the dealer banks have access to this information. Concerns about the lack of price transparency are growing as banks continue to increase their presence in these markets as dealers, arrangers, underwriters, and investors. Further, with the increasing use of fair value accounting, the pricing of these complex securities directly affects bank earnings and regulatory capital.

Investors, regulators and other interested parties need to focus attention on the lack of liquidity in most structured finance offerings and work toward improving price discovery. Regulators should encourage market participants to openly share trading information about ABS and CDOs, such as daily volumes, bid/ask spreads, consensus prices, and price ranges and report this information to pricing services. Indeed, the industry should look to the publication of corporate bond information in daily business newspapers, such as The Wall Street Journal and Financial Times, as an example of transactional transparency.

Regulators need to reevaluate the supervisory treatment of ABS and CDOs that are not liquid and do not trade on active secondary markets to ensure the risks associated with these securities are adequately captured in the examination process and in capital regulation. High credit ratings should not be viewed as a substitute for adequate due diligence on the part of the bank or for adequate supervision by the examiner. Bank management must have a thorough understanding of the terms and structural features of the structured finance products that they hold for investment. For example, bank management should know the type of exposures that collateralize the product, the credit quality of the underlying exposures, the methods by which the product is priced, and the key assumptions affecting its value.

Private Placements

Historically, private placements of corporate bonds arose as a way to reduce the cost of the securities registration process for companies with an established track record. The rationale for allowing private placements seems less compelling with securitizations. In contrast to corporate bonds, securitizations consist of various pooled securities, including MBS and CDOs, that often have no track record and that require an in-depth modeling and understanding of a highly segmented amount of assets that comprise the collateral pool. For this reason, a lack of complete and public dissemination of a securitization’s loan-level data reduces transparency and hampers the investor’s ability to fully assess risk and assign value.

The practice of private issuance creates difficulties in obtaining deal-specific information for many analysts, including regulators and academics. As an example, most if not all CDOs typically are issued in private offerings. These offerings are exempt from registration and significant disclosure requirements of the Securities Act of 1933.

Because underwriters of structured finance products typically do not provide significant disclosure under Rule 144A issuances, there is a danger that negative information may be muffled to obtain the best market pricing for the structure. This has the direct effect of improving the profitability of the security underwriter and improving the marketability to both sides of the transaction: the loan originators and security investors. As long as these securities perform, investors are not likely to question their transparency.

The SEC adopted new and amended rules and forms to address the registration, disclosure, and reporting requirements for ABS, referred to as Reg AB. Some consideration should be given to extending the disclosure requirements under Reg AB to all Rule 144A and private placement securities.

Banking regulators should consider other approaches in concert with the review of securities registration and disclosure enhancements. For instance, banking regulators should consider whether the capital treatment of structured finance products could be conditioned on the granularity and the quality of information provided in prospectuses and offering circulars, even if the bank is considered to be a qualified institutional buyer.

Vendor Product Shortcomings

Securitization documentation, such as offering circulars, indentures, and trustee reports, are available only to dealers and certain qualified investors.9 For this reason, some vendors collect, package, and sell this information. However, the price and complexity of vendor models and limitations to the informational disclosure do not eliminate the high hurdle to investors, analysts and academics—and regulators—wishing to analyze this sector.

A more comprehensive definition of interested parties should be considered. Regulators are responsible for ensuring the safety and soundness of financial institutions—and the banking system generally. Therefore, regulators must be able to quickly collect information that cuts across an entire industry or segment, rather than just an individual bank. To provide regulators with the tools needed to evaluate the capital markets as a whole, any restrictions that limit a regulator’s ability to ascertain necessary market information should be reevaluated. The SEC could—and should—modify its definition of a qualified institutional buyer through rulemaking to include regulators.

Rating Agency Disclosure of Securitization Information Lacking

Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (NRSROs) rate securitization tranches to publish an opinion about the creditworthiness of these instruments. Such ratings have been criticized for being one dimensional in a multi-dimensional securitization world of risk. In the case of CDOs, agencies rate the notes but may not provide complementary information.

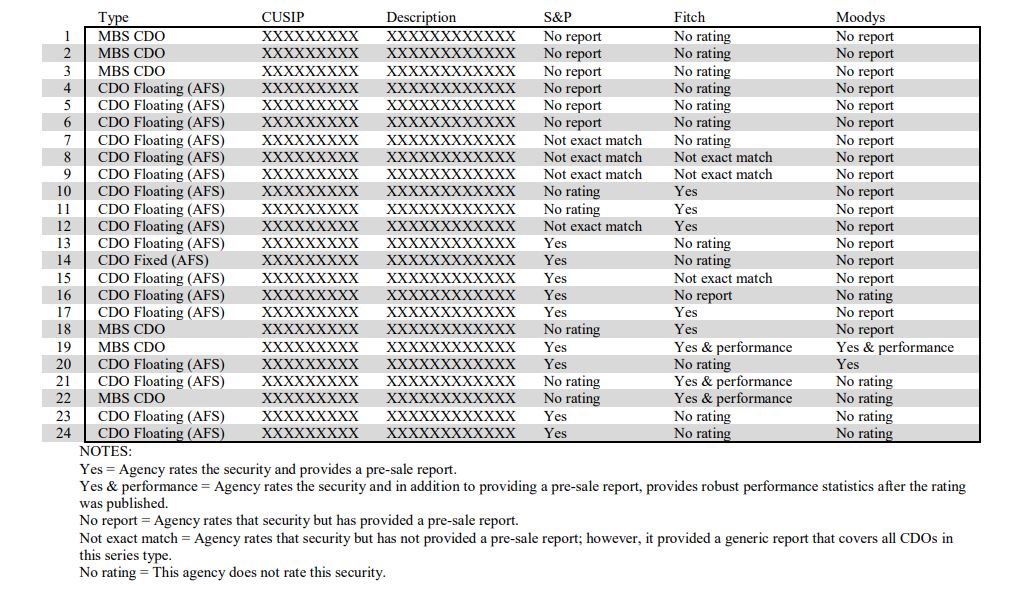

Table 1 provides a listing of a representative sample of CDOs reviewed by the FDIC in the course of its risk assessment activities relative to insured institutions. The table shows that of 24 CDOs reviewed, slightly more than half had a presale report that was made publicly available by an NRSRO. Further, for the same 24 CDOs, only 3 had robust performance data published by an NRSRO.

Table 1: NRSRO Disclosure about CDOs is Limited

The SEC should review the quality and granularity of information provided on the rating agencies’ public Web sites. Rating agencies should be strongly encouraged to provide information on all aspects of a rated transaction, including loan-level information on the underlying collateral. Surveillance reports should be issued regularly and should note any material changes to the composition of the securitization vehicle.

Regulators also will need access to more granular information as part of the Basel II implementation process. Under the Internal Assessment Approach and the Supervisory Formula, regulators will need to have loan- and portfolio-level information to evaluate the appropriateness of the capital requirements. The regulators should begin a dialogue with the rating agencies to determine if enhancements to the transparency of the ratings process could also provide value to Basel II implementation efforts.

Rating Agency Impact on Transparency

In many respects, NRSROs have contributed to transparency concerns. For example, NRSROs have been criticized for assigning inconsistent ratings across different business sectors. At the extreme, during a recent event related to credit rating agency performance, a panel speaker suggested that for a given rating, CDOs were 250 times more risky when compared to municipal securities.10 Even before problems with subprime mortgages emerged in late 2006, according to a Moody’s presentation, all structured finance securities were likely to be downgraded on average by 3 notches, twice as severe as the 1.5 average downgrade for corporate securities.

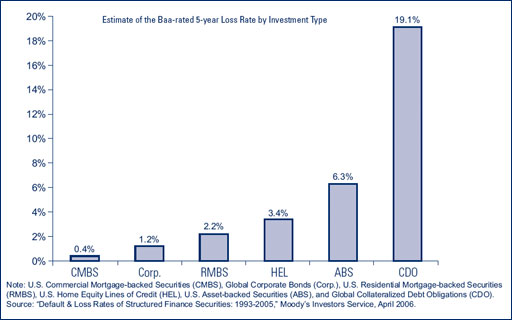

In addition, ratings assigned to structured finance products generally have a much worse credit track record than corporate bond ratings. For instance, as shown in Chart 1, the estimated 5-year loss rate for a Baa-rated (BBB-rated on the S&P scale) CDO is about 16 times the estimated loss rate for a Baa-rated corporate bond. Thus, two exposure types with identical ratings can have drastically different loss expectations.

Chart 1: Most Investment Grade Securitizations Performed Poorly Compared to Corporates

Nonetheless, credit ratings do provide useful information to investors, as do reports and other information provided by NRSROs. This information is especially useful in judging the loss expectation of one instrument relative to another within a specific product type. However, as discussed earlier in this article, it is especially important for investors to understand the limitations of credit ratings and to use them accordingly, as one component in the due diligence process along with an independent analysis of the risks associated with the pool of assets used as collateral.

Rating Agencies’ Attempt at Improving Transparency and Disclosure

The rating agencies have recognized that the lack of transparency in the structured finance market has contributed to current problems and have begun to reevaluate the ratings process. For example, on September 25, 2007, Moody’s proposed a series of enhancements to the Non-Prime RMBS Securitizations11 that they believe, if adopted, would improve the transparency and oversight on loans sold into a securitization vehicle. Generally, the Moody’s proposal is intended to address the need for third-party loan reviews, improve representations and warranties, and enhance reporting for increased transparency.

The enhancements proposed by Moody’s would help increase transparency. However, transparency cannot be increased industry wide unless the SEC, as the regulator of NRSROs, endorses proposals such as this as a best practice and factors the standards into its supervisory oversight function. Ideally, all rating agencies would follow and provide more granularity on the underlying exposures in their publicly available presale and surveillance reports so that investors, regulators, and other interested parties can better assess the risks relating to these securities.

President’s Working Group’s Objective to Improve Transparency

In March 2008, the President’s Working Group on Financial Markets (PWG) issued a report that included several recommendations designed to address weaknesses in the financial markets—weaknesses which the PWG believe to be significant contributing factors to the recent market turmoil.12 In this report, the PWG notes the need to improve transparency and disclosure and develop better risk awareness and management to “mitigate systemic risk, help restore investor confidence, and facilitate economic growth.”13

This call for greater transparency includes a challenge to credit rating agencies to increase the transparency of the ratings and foster the appropriate use of ratings in the risk assessment process.14 Similarly, the accounting profession is challenged to increase the transparency of U.S. accounting standards as they relate to consolidation and securitization.

Investors Play a Key Role in Demanding Improved Transparency

Investors need to look beyond the ratings and develop a better awareness of the risks to which they are exposed. They should demand exposure-level information on the performance and composition of underlying assets as well as on the structural features that can quickly alter the terms of the deal. For example, much concern has been raised about SIVs and the possibility that adverse events (“triggers”) could result in the unwinding of several of these large funds and the dumping of tens of billions of securities onto an already uncertain market. Yet, few people possess sufficient information on how the triggers work, how close they are to being breached, or what action a sponsor would take, depending on the type and severity of the breached trigger. Uncertainty could result in confusion and panic; improved disclosures would mitigate this confusion.

Efforts should be made to require financial firms to provide sufficiently detailed information about triggers and other events that could result in an unwinding of the securitization transaction or other changes to the underlying economic benefits. Any such changes to disclosure requirements would need to be addressed by the SEC through its regulatory rulemaking process; however, regulators and rating agencies could provide beneficial support by encouraging firms to voluntarily make such disclosures.

Further, investors should also take into consideration the amount of financial support that is expected to be provided by the financial firm that sponsors a structured finance transaction, regardless of whether it is contractually obligated to provide liquidity or credit enhancements. The risk exposure to financial firms that results from this activity may not be fully appreciated by investors in those firms, or by investors who rely on the ability of those firms to provide the contractual support. Greater transparency in the financial reporting of all firms engaged in structured finance could serve to enhance transparency of the full spectrum of risks that are associated with the structured finance market.

Supervisory Considerations Regarding the Use of Investment Ratings

Two significant factors in the recent market turmoil have been the over-reliance on credit ratings and a misunderstanding of what those ratings mean. Longstanding supervisory guidance specifies that while banks can consider credit ratings as a factor in the risk management process, ratings should not be the sole factor considered when evaluating the risks of investing in securities.

The FDIC’s Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies includes a sub-chapter titled Securities and Derivatives which references the banking agencies’ 1998 Supervisory Policy Statement on Investment Securities and End-User Derivatives Activities15 and the Interagency Policy on Classification of Assets and Appraisal of Securities.16 FDIC-supervised banks should be familiar with the Manual of Examination Policies and each of these policies, as they remain in force.

Credit ratings should not be used as a substitute for pre-purchase due diligence or as a proxy for ongoing risk monitoring for banks with positions in complex securities. Banks should understand that the loss expectations associated with the rating scales used by credit rating agencies for various types of debt (corporate bonds, structured finance investments, and municipal debt) can differ. For example, the expected loss for a given rating may vary across products as does the volatility of ratings (as reflected by transition matrices) assigned.

Credit ratings do not capture all of the risks which should be considered during the risk management process, such as loss given default, the potential for downgrade (also known as ratings volatility risk), market liquidity, and price discovery. In many types of structured finance securities, these “other” risks can be material and can be the source of a significant degree of losses. The analysis of complex securities, such as CDOs, is particularly difficult, and potential buyers should be aware that the rating agencies and others may underestimate difficult-to-measure risk factors, such as correlation.

Banks should conduct pre-acquisition and periodic analysis of the price sensitivity of securities. Risk factors include, but are not limited to, changing interest rates, credit risk deterioration, and reduced liquidity and marketability. Banks should anticipate difficulty when attempting to price illiquid and complex securities, and should limit concentrations of such holdings.

The 1998 Supervisory Policy Statement on Investment Securities and End-User Derivatives Activities provides guidance and sound principles to bankers for managing investment securities and derivatives risks. It makes clear the primary importance of board oversight and management supervision, and focuses on risk management, controls, and reporting. Management should approve, enforce, and review policy and procedure guidelines that are commensurate with the risks and complexity of bank investment activities.

The interagency Policy Statement emphasizes management’s need to understand the risks and cash-flow characteristics of its investments, particularly for products that have unusual, leveraged, or highly variable cash flows. The Policy Statement also states that banks must identify and measure risks, prior to acquisition and periodically after the purchase of securities, and that management should conduct its own in-house pre-acquisition analyses, or to the extent possible, make use of specific third-party analyses that are independent of the seller or counterparty.

Bobby R. Bean

Chief, Policy Section

Division of Supervision and Consumer Protection

BBean@fdic.gov

Appendix A

Overview of the Securitization Process

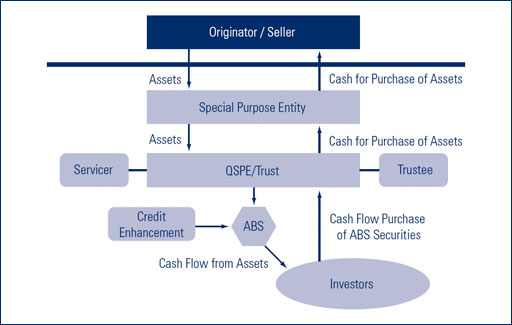

In general, a securitization is the issuance of a financial instrument backed by the performance of identified assets where the investor has no recourse to the originator or seller of the asset. The typical securitization structure uses a two-step process that involves an originator/seller establishing a bankruptcy-remote special purpose entity (SPE). The originator then sells the assets that will serve as collateral for the asset-backed securities (ABS) to this SPE in order to attain true-sale accounting treatment and remove the assets from its balance sheet. To meet the provisions of FAS 14017 the assets are often transferred to a second entity, a Qualified SPE (QSPE) or trust, that then issues the securities. Chart 1 illustrates this process for a simplified, generic securitization transaction.

Chart 1: A Simplified Overview of the Securitization Process

Appendix Chart 1 Description

This two-step process is followed to legally separate the collateral from the general assets and obligations of the originator. This separation ensures that the assets serving as securitization collateral cannot be consolidated with the general assets of the originator in the event of bankruptcy. The bankruptcy remoteness of the assets allows the securitization structure to achieve a higher credit rating than that of the originator. The issuer is able to achieve its desired credit rating by incorporating varying levels and forms of credit enhancement.

For issuers, the securitization process removes assets from the balance sheet, freeing equity capital that would otherwise be required to support those assets. Issuers of securitizations are also able to manage credit risk and other risk exposures, such as interest rate risk, by removing from the balance sheet assets that represent unwanted risk and dispersing the risk to securitization investors within the financial market. The securitization process also provides issuers access to a new funding source and a vehicle with which to enhance income and return on assets. This is accomplished through the combination of receiving income from the sale of the assets and the simultaneous reduction in asset size.

The securitization process provides investors with several benefits over the origination, or purchase, of the assets individually. One fundamental benefit is the redistribution of risk. The tranching process, which is made possible through the pooling of assets, allows the various risks and characteristics inherent in the individual assets to be segregated, manipulated, and tailored. At least in theory, investors are able to select the specific risk-and-reward profile that best matches their objectives, including maturity, interest rate risk, prepayment risk, extension risk, and yield. Securitizations also offer diversification, as the underlying assets include a number of different obligors that are geographically dispersed and often originated by a number of different entities. When they are secured by appropriately underwritten credit exposures, securitizations can provide a high quality investment.

Selected Definitions

Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO).

A CDO is a financial security that has collateral that consists of one or more types of debt, including corporate bonds, corporate loans, and tranches of securitizations.Structured Investment Vehicle (SIV).

An SIV is a special purpose entity (including a business trust or a corporation) with assets that consist primarily of highly rated securities. The assets are financed through the proceeds of commercial paper and medium-term note issuances.

1 This article was commissioned by FDIC Chairman Sheila C. Bair and is intended to highlight policy issues associated with improving the transparency of certain securitization products for consideration by financial institution regulatory agencies and bank management.

2 For example, the Bond Market Association, now the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, or SIFMA, Mortgage Securities Research Committee, published the first Standard Formulas guidelines in 1990

3 See Appendix A for an overview of the securitization process and selected definitions.

4 Daniel Pimlott, “Municipal SIV Advocates Fly into Turbulence,” Financial Times, December 16, 2007, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/cb60a480-ac0b-11dc-82f0-0000779fd2ac.html.

5 David Evans, “Public School Funds Hit by SIV Debts Hidden in Investment Pools,” Bloomberg News, November 15, 2007, http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601170&refer=home&sid=aYE0AghQ5IUA

6 Congress held hearings soon after the failure of Enron to determine the extent to which banking entities assisted in concealing Enron’s true financial condition by arranging complex structured finance transactions. Senior staff at the Federal Reserve Board, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) testified at these hearings. At these hearings and in subsequent correspondence, it was agreed that further guidance was necessary to ensure that banks maintain the proper controls for governing these activities in order to prevent abuses like those perpetrated by Enron, WorldCom, Parmalat, and others. On January 11, 2007, the federal banking agencies, along with the SEC (agencies), issued a final interagency statement (FIL-3-2007, “Complex Structured Finance Activities Interagency Statement on Sound Practices for Activities with Elevated Risk”) that describes some of the internal controls and risk management procedures that may help banks identify, manage, and address the heightened reputational and legal risks that may arise from elevated-risk Complex Structured Finance Transactions. The statement does not apply to products with well-established track records that are familiar to participants in the financial markets, such as traditional securitizations.

7 Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745.

8 SEC Regulation AB (Registration Requirements for Asset-Backed Securities): 17 CFR 229.1100 through 1123.

9 Vendors of CDO and hedge fund data sometimes require that customers meet certain investment standards before gaining access to information. These rules in essence intend to keep smaller undiversified investors from accessing more sophisticated investments. However, the FDIC’s not meeting certain standard investor definitions may hamper its regulatory research efforts. Such definitions may be identified under some documents, such as the Securities Act of 1933 or the Investment Company Act of 1940, and may include the terms Accredited Investor, Accredited Institutional Investor, Qualified Purchaser, and Qualified Institutional Investor or Buyer. Links to some working definitions include http://www.sec.gov/answers/accred.htm and http://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/33-8041.htm.

10 Is the Rating Agency System Broken or Fine?” Presentation given by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, November 15, 2007, https://www.aei.org/events/is-the-rating-agency-system-broken-or-fine/.

11 Nicolas Weill, “Moody’s Proposed Enhancements to Non-Prime RMBS Securitization,” Special Report, Moody’s Investors Service, September 25, 2007.

12 The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, “Policy Statement on Financial Market Developments,” March 2008.

13 Henry M. Paulson, Jr., “Memorandum for the President, Regarding President’s Working Group on Financial Markets Policy Statement,” March 13, 2008.

14 The President’s Working Group on Financial Markets, p. 17.

15 Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), “Policy Statement on Investment Securities and End-User Derivatives Activities,” 63 FR 20191, April 23, 1998.

16 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FIL 70-2004, Interagency Policy on Classification of Assets and Appraisal of Securities, June 15, 2004, at https://www.fdic.gov/news/inactive-financial-institution-letters/2004/fil7004.html.

17 FAS 140 provides that the assets and liabilities of a Qualifying Special Purpose Entity (QSPE) do not get consolidated into the financial statements of the transferor. For more information, see Financial Accounting Standards Board, Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 140, September 2000.