Introduction

Leveraged lending provides credit to commercial businesses with higher levels of debt and also helps companies obtain funding for transactions involving leveraged buyouts (LBOs), mergers and acquisitions (M&A), business recapitalizations, and business expansions. Many commercial businesses successfully utilize and repay these loans; however, high debt levels coupled with lower levels of liquidity may reduce businesses’ flexibility to respond to changes in economic conditions. The recent period of economic expansion combined with low interest rates provided companies with the opportunity to increase their debt levels over the past decade. As a result, more businesses sought, and received, leveraged loans.

The FDIC recognizes the important role that leveraged lending has in the global market economy, as well as the important role insured depository institutions (IDIs) serve in providing credit to companies through originating and participating in leveraged loans. Underwriting and bank risk-management practices are expected to be commensurate with the potential heightened risk associated with this type of lending, and IDIs and the leveraged-lending market as a whole benefit from the origination of soundly underwritten loans.1

The FDIC and other Federal Regulatory Banking Agencies (FBAs) closely monitor industry leverage trends, and banks’ underlying risk- management practices associated with this type of lending.

The interagency Shared National Credit (SNC) Program is conducted twice each year and is a primary mechanism for the FBAs to monitor leveraged lending in IDIs related to portfolio growth, underwriting trends, and risk management practices. A SNC is defined as a loan greater than $100 million made by three or more institutions, which includes various types of loans, in addition to leveraged loans. The FBAs publish annual results of the combined semi- annual SNC review, which includes details on leveraged lending trends and associated risks. The FBAs also conduct targeted examinations of leveraged lending activity in addition to ongoing supervision to assess risk in this area.

Both bank and non-bank entities are involved in leveraged debt financing. Banks held approximately 63 percent of leveraged loan commitments in the SNC portfolio as of December 31, 2018, compared to 37 percent held by non-banks. This article focuses primarily on exposure in the banking sector, and the content is based on observations from SNC results and examination findings at FDIC- supervised IDIs.

Leveraged Lending Defined

Leveraged lending has no universal definition and is not defined in exact terms by regulatory agencies. Supervisory guidance establishes a range of potential criteria,2 and IDIs generally consider overall borrower risk, loan pricing, and measures of leverage (in terms of debt to income) when defining leveraged credits within bank policies. Credit rating agencies typically define leveraged lending as loans rated below investment grade level, which is categorized as Moody’s Ba3 and Standard & Poor’s BB-, or lower, and for loans to non-rated companies that have higher interest rates than typical loan interest rates.

The SNC program tracks leveraged lending based on information reported by IDIs, and therefore accurate reporting by institutions is critical. As disclosed in the January 2019 SNC public statement, bank-reported leveraged credits in 2018 totaled approximately $2.1 trillion, of which $700 billion was investment grade. This level is consistent with the leveraged loan market size noted by the rating agencies at $1.2 to 1.3 trillion, which excludes investment grade.

Leveraged Lending Risk

Results from SNC reviews have highlighted building risk in terms of dollar volume and loan structures. In 2014, the FBAs issued a “Leverage Lending Supplement” that highlighted underwriting and risk management weaknesses in this sector.3 Since then, risk management practices have improved significantly at most IDIs involved in structuring and underwriting leveraged transactions. However, credit structures themselves have continued to weaken reflecting heightened demand for leveraged credit and non-bank preferences on terms. Findings from the 2018 SNC review,4 state that “many leveraged loan transactions possess weakened transaction structures and increased reliance upon revenue growth or anticipated cost savings and synergies to support borrower repayment capacity.” IDIs purchasing leveraged loans should be fully aware of the risk and possess the skills to measure, monitor, and control it.5

The increased risk in leveraged lending is illustrated in the volume of leveraged loans that are listed for Special Mention6 or subject to adverse classification by the FBAs. Of the $295 billion in Special Mention6 and adversely classified loans within the total $4.4 trillion SNC portfolio, leveraged loans comprise 73 percent of special mention commitments, 87 percent of substandard7 commitments, 45 percent of doubtful8 commitments, and 76 percent of non-accrual9 loans. A material downturn in the economy could result in a significant increase in classified exposures and higher losses.

Non-bank investors in leveraged loans are primarily collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), pension funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and managed funds. These entities have increased their participation in the leveraged-lending market via purchases of loans or direct underwriting and syndication of exposure and more leveraged lending risk is being transferred to these entities. This trend and heightened competition have caused a shift from traditional IDI loan structures. In order to satisfy investment demands, banks began to structure leveraged lending products that more closely resemble a bond than a corporate loan. For example, leveraged term- loans carry few if any financial- maintenance covenants. Additionally, these loans often require only minimal debt amortization, which underscores that the likely repayment source is debt refinance.

Large IDIs that syndicate and arrange a majority of the leveraged loans hold few if any of these term-loan facilities on their books, but often provide funding for the revolving- credit facilities. A revolving credit facility provides the borrower with the flexibility to draw down, repay, and withdraw again. During an allotted period of time, the facility allows the borrower to repay the loan or take it out again. While IDIs traditionally arrange and distribute leveraged loans, and serve as administrative agents- for those loans, non-bank direct lenders have become more involved in originating and syndicating leveraged loans in recent years.

Effective Risk Management

The Interagency Guidelines Establishing Standards for Safety and Soundness10 (Guidelines) outline the standards the FDIC uses to identify and address potential safety and soundness concerns and ensure action is taken to address those concerns before they pose a risk to the Deposit Insurance Fund. The Guidelines set forth a framework for appropriate risk management that can be applied to leveraged lending based on the size of the institution and the nature, scope and risk of its activities.

Among other expectations, the Guidelines state that an institution should have:

- internal controls and information systems that provide for effective risk assessment; timely and accurate financial, operational, and regulatory reports; and adequate procedures to safeguard and manage assets;

- loan documentation practices that enable the institution to make an informed lending decision and to assess risk, as necessary, on an ongoing basis; identify the purpose of a loan and the source of repayment, and assess the ability of the borrower to repay the indebtedness in a timely manner; demonstrate appropriate administration and monitoring of a loan; and take account of the size and complexity of a loan;

- prudent credit-underwriting practices that are commensurate with the types of loans the institution will make and that consider the terms and conditions under which they will be made; consider the nature of the markets in which loans will be made; provide for consideration, prior to credit commitment, of the borrower’s overall financial condition and resources, the financial responsibility of any guarantor, the nature and value of any underlying collateral, and the borrower’s character and willingness to repay as agreed; establish a system of independent, ongoing credit review and appropriate communication to management and to the board of directors; take adequate account of concentration of credit risk; and are appropriate to the size of the institution and the nature and scope of its activities; and

- a system to identify problem assets and prevent deterioration in those assets; conduct periodic asset- quality reviews to identify problem assets; and provide periodic asset reports with adequate information for management and the board of directors to assess the level of asset risk.

Risk management programs for IDIs that originate or arrange leveraged loans or participate in a large volume of leveraged loans should be more fully developed and comprehensive versus IDIs whose leveraged lending activities are limited in volume and size relative to its overall capital and reserves.

Underwriting Trends

In accordance with the Guidelines, IDIs are expected to develop policies and procedures that identify and measure risk, monitor leveraged credit, and implement sound underwriting and risk management practices. As mentioned, leveraged loan volume has increased and loan structures have weakened. This trend has, in part, been driven by increased competition for such products, as well as by the increasing fees generated by originating these credits. Examination data shows that some IDIs have purchased participations in leveraged loans without fully assessing the risk or developing appropriate policies and procedures.

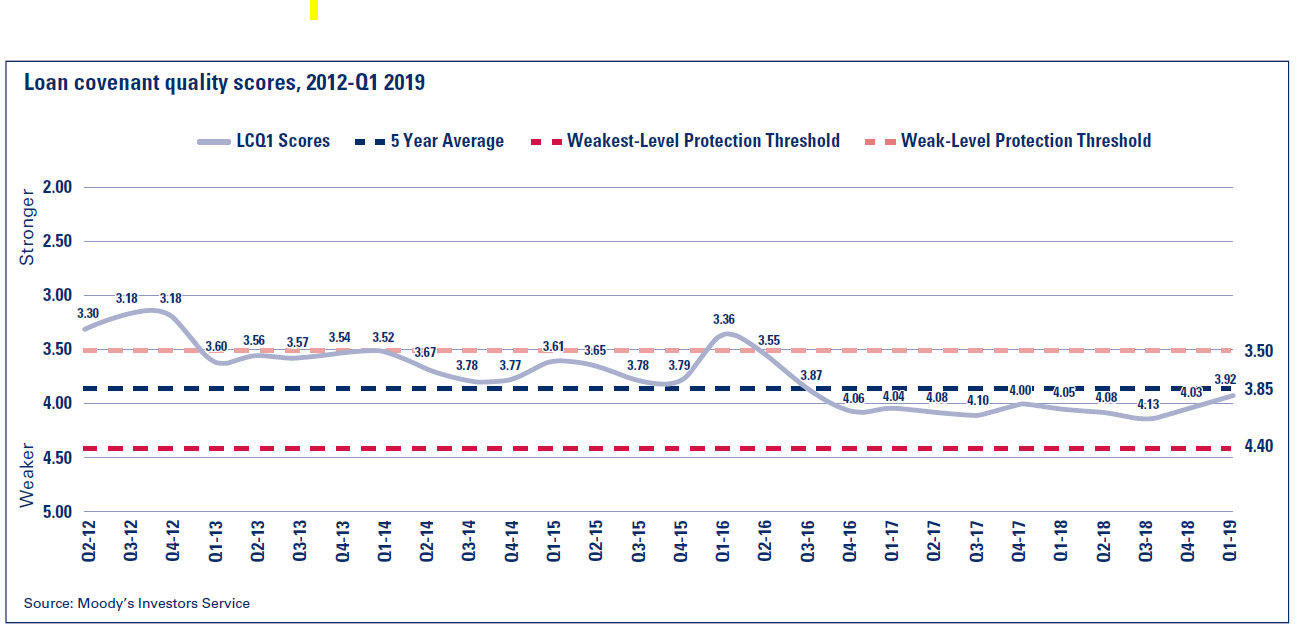

In recent years, lenders have allowed covenant protections to erode. This trend results in fewer lender protections. This point is illustrated by Moody’s in its Loan Covenant Quality Indicator (LCQI) graph of newly originated leveraged loans as noted in Moody’s Investors Service press release dated April 24, 2019. and is supported by published findings of annual SNC reviews.

Since 2012, Moody’s has tracked the quality of covenants in newly originated loans for the quality of financial covenants, structural priority, restrictive payments, debt issuance, investment and asset sales, and general lender rights. The graph illustrates the weaker trend of covenant protection since 2016, which highlights the risk faced by IDIs lending to leveraged borrowers.

As mentioned previously, the 2018 SNC review found that leveraged loan transactions possessed weakened transaction structures that may limit borrower repayment capacity, and by extension, cause losses at IDIs. These weaknesses are discussed more fully below.

Capital Structure and Lender Priority

Leveraged borrowers use a variety of debt and equity to fund acquisitions, asset purchases, dividends, and refinancing transactions. IDIs typically provide all of the first lien senior secured revolving lines of credit as well as some of the first lien senior secured term loans in leveraged transactions. As mentioned, leveraged first lien term loans may have limited amortization requirements. Junior debt facilities typically require no amortization.

The capital structure may also include junior debt such as senior secured bonds, subordinated mezzanine debt, or other hybrid equity facilities that only require interest payments or payment- in-kind (PIK). Junior debt has historically provided additional protection to senior secured lenders; however, the protection has declined in recent years, as more leveraged- loan transactions contain only first lien senior secured debt in the capital structure.

This trend implies greater reliance on lender protections, which include the value of the entity as a going concern, the value and quality of collateral, support from sponsors and guarantors, and covenant protections. Most leveraged loans are secured by all business assets and common stock of the company (Enterprise Value), which results in valuing the company based on its ability to generate recurring cash flow. Accordingly, the value of a company can rapidly fluctuate. Examinations have identified instances in which IDIs failed to adequately monitor enterprise value, or where enterprise valuation methodologies were inadequate. Failure to monitor this lender protection could result in insufficient reserves in the event of borrower default.

Repayment Capacity

Effective analysis of a leveraged borrower’s debt repayment capacity can be challenging due to the complex capital structures and rapid growth strategies that are typical in leveraged lending. IDIs develop models and analyze repayment capacity using cash flow assumptions developed by the borrower or sponsor. Examiners carefully scrutinize assumptions promoting overly aggressive EBITDA add-backs that do not reflect a ‘most likely’ scenario in IDI repayment models, and have identified instances in which repayment modeling is not well supported or overly aggressive.

Credit Agreement Protections

The loosening of terms within credit agreements in recent years presents a heightened level of risk for IDIs. For example, many credit agreements allow borrowers the right to obtain additional debt without the current lender’s approval, an ability known as incremental facilities. The additional incremental debt can result in elevated leverage and dilute collateral protection.

Financial-maintenance covenants are also becoming rare in leveraged- loan structures. Financial- maintenance covenants play a vital role as an early warning sign of deterioration in a leveraged borrower. For many newly originated leveraged- loan transactions, protection consists of “springing” covenants that limit the use of revolving credit facilities only after the revolver is drawn to a specified level.

Leveraged-loan credit agreements are also structured to allow a borrower the ability to sell, transfer, and purchase assets in the normal course of typical operations, which can expose lenders and investors to reduced cash and collateral protection and can affect repayment and refinancing risk. Recent examples include companies that have used these “carve-outs” from the collateral pool to move business lines and intellectual properties to affiliates of the borrower, which resulted in lower potential borrower enterprise value.

Leveraged-loan credit agreements often require a certain agreed-upon amount of excess cash to be used to pay debt, but carve-out provisions in recent credit agreements often allow cash to be used for dividends, investments, capital expenditures, and other purposes before being included in the excess cash flow calculation that is used to determine the amount for debt repayment.

Examiners have identified cases of limited identification and assessment of these types of underwriting and credit agreement weaknesses, which can minimize the efficacy of credit risk grading, understanding of portfolio risk, and appropriateness of loan and lease loss reserves.

Loan Review

An effective loan review structure serves to mitigate leveraged-lending risk, and given the complexities and risk inherent within a leveraged-loan portfolio, the scope and independence of the process is critical. A common scope may include consideration of the reasonableness of cash flow projection assumptions, adequacy of loan stress testing, compliance with covenants, adequacy of enterprise valuations, and ultimately the accuracy of the credit rating.

Examinations have identified instances in which loan review frequency, depth, and quality has been insufficient to provide a strong independent assessment of credit administration and underwriting relative to leveraged lending. Further, in some other instances, loan review staff or outsourced loan review personnel were not trained to assess the unique credit characteristics of leveraged borrowers.

Syndications, Participations, and Sub-Participations

Leveraged loans can be purchased directly from agent banks or indirectly through third parties such as bankers’ banks or non-bank financial institutions. Third-party providers can provide smaller investment amounts for IDIs, as well as provide other fee-based services. Third-party providers can also assist with the risk management function, generally for a fee, which can include help with underwriting, risk rating, enterprise valuations, and ongoing credit review.

Outsourcing any risk management function comes with risk, and examinations have identified situations where IDIs have become overly reliant on the vendor. IDIs are expected to maintain sound vendor management programs when purchasing leveraged loans from a third party, which includes independent analysis of each credit.

Management and Board Oversight

The establishment of effective risk tolerance, measurement, and reporting is critical. Examinations have identified instances in which policies and procedures do not have clear portfolio and capital limits on the volume and type of leveraged credits, including limits to any single leveraged borrower. Examinations have also identified instances in which policies and procedures are inadequate in terms of monitoring and risk-ranking leveraged credits.

Summary

Leveraged lending presents heightened risk for IDIs if internal risk management programs are not established and effectively managed. Leveraged lending volumes, held by banks and non-banks, have continued to increase. As a result, regulatory scrutiny of this sector will continue.

Gary L. Storck

Senior Large Financial

Institution Specialist

Division of Risk Management Supervision

Gstorck@fdic.gov

Mark D. Sheely

Senior Large Financial

Institution Specialist

Division of Risk Management Supervision

MSheely@fdic.gov

1 See e.g., the Interagency Safety and Soundness Standards in Appendix A of Part 364 of the FDIC’s Rules and Regulations, and the risk management practices outlined in the Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending.

5 The Interagency Safety and Soundness Standards in Appendix A of Part 364 of the FDIC’s Rules and Regulations, as required by Section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, addresses the importance of prudent credit underwriting, loan documentation requirements, and asset quality controls and monitoring practices. In addition, IDIs engaged in leveraged lending should be aware of the risk management practices outlined in the Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending.

6 Special mention commitments have potential weaknesses that deserve management’s close attention. If left uncorrected, these potential weaknesses could result in further deterioration of the repayment prospects, or in the institution’s credit position in the future. Special mention commitments are not adversely rated and do not expose institutions to sufficient risk to warrant adverse rating.

7 Substandard commitments are inadequately protected by the current sound worth and paying capacity of the obligor or of the collateral pledged, if any. Substandard commitments have well-defined weaknesses that jeopardize the liquidation of the debt and present the distinct possibility that the institution will sustain some loss if deficiencies are not corrected.

8 Doubtful commitments have all the weaknesses of commitments classified substandard and when the weaknesses make collection or liquidation in full, on the basis of available current information, highly questionable or improbable.

9 Nonaccrual loans are defined for regulatory reporting purposes as loans and lease-financing receivables that are required to be reported on a nonaccrual basis because (a) they are maintained on a cash basis owing to a deterioration in the financial position of the borrower, (b) payment in full of interest or principal is not expected, or (c) principal or interest has been in default for 90 days or longer, unless the obligation is both well secured and in the process of collection.